Below is a list of wonderful books to warm you up on a cold day or night. Curled up under a quilt, I read them while sipping hot tea, hot chocolate, or the occasional cold beer. I loved each of these books. (Listed alphabetically by author’s last name.)

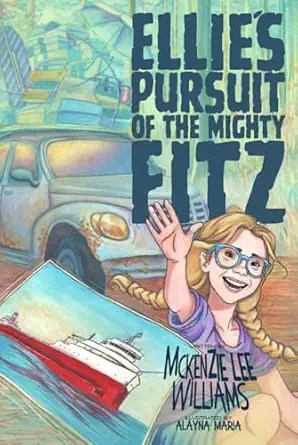

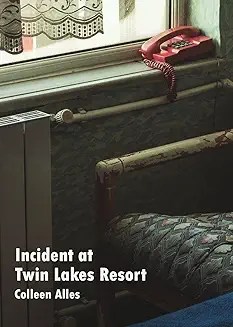

Incident at Twin Lakes Resort by Colleen Alles is a fast-paced, thought-tickling, engaging novella.

It’s Labor Day weekend in Michigan. Cassie, a naive twenty-one-year-old senior in college meets up with her new boyfriend, Ethan, at a rustic lodge on the shores of a sparkling, picturesque lake. They’ve only been dating for a New York minute, but he invites her to be his plus-one for the holiday weekend at a retreat sponsored by the law firm where he works. The firm’s getaways are designed to give employees a chance to bond. Cassie, who is excited to be invited to the retreat, quickly discovers most of Ethan’s coworkers and spouses are jaded by their past experiences at the outings. Her hopes for a romantic weekend with Ethan are dashed by the drunkenness, back-biting, and cynicism of his coworkers, and Ethan’s hot-and-cold behavior. Looking for kindness and connection, Cassie befriends a new mother with an infant and one of Ethan’s male coworkers, who has come to the retreat alone.

I loved this book because while it might read like a placid little story about a disappointing romantic weekend, it has thematic chops. We are asked to think about the choices we make, about what it means to be happy, and about how success is measured. Alles’s choice of Cassie, a naive young woman, to narrate the story is perfect. She is the fish-out-of-water character in this story. She is youthful innocence peering into the world of jaded adulthood.

Incident at Twin Lakes Resort won the Etchings Press novella prize in 2025, and was published by that press at the University of Indianapolis.

33 Place Brugmann, a novel by Alice Austen, takes readers back to 1939. Nazis and fascists, after stripping people of their freedoms and humanity, plunge the world into WWII. As they conquer Europe and send people to death camps, readers can’t help but think of current times and ask themselves, “Can this happen again?”

The story begins in Brussels just before the Nazis invade and occupy Belgium in May 1940. It follows the lives of fourteen residents who live in the apartment building at 33 Place Brugmann. The Raphaëls, a Jewish family of four disappear during the night, along with Mr. Raphaël’s art collection. Masha Balyayeva, a Jewish refugee from Russia, soon leaves for France, where posing as a Christian, she joins the French Resistance. The Everards, DeBaerres, Colonel Warlemont, Miss Hobert, and Sauvins remain at 33 Place Brugmann. War, hunger, and fear reveal the best and worst in the residents. As WWII drags on, Jewish people are arrested and transported, food shortages worsen, and bombs fall. The remaining non-Jewish residents of 33 Place Brugmann still have plenty to fear. Perhaps a neighbor or co-worker will turn them into the Nazis because of something they’ve said or done. Who can they trust? Who might betray them?

I loved this book because of its tightly-woven plot, its beautiful writing, and its richly-drawn characters. My favorite character is Charlotte Sauvin, who is seventeen years old when the story begins. I also loved this book because it accomplishes what excellent historical fiction should always do — make readers reflect on current times and timeless themes while learning about the past.

Recognition for 33 Place Brugmann — A New York Times Editor’s Choice, Shortlisted for the National Jewish Book Award, and Longlisted for the 2026 PEN/Hemingway Award.

The Book of Ruth, a novel by Jane Hamilton

“Weddings don’t have one thing to do with real life” (p. 143). This one quote says it all and could easily be the tagline for Hamilton’s deeply moving story.

This novel is a literary delight. It’s a bit of William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and a bit of John Williams’s Stoner and a whole lot of its own hauntingly told tale. Ruth narrates the story, and through her Hamilton creates an astonishing voice. Readers follow Ruth through her relationship with her mother, May, then with her husband, Ruben, whom everyone calls Ruby. After Ruth marries Ruby, they live with Ruth’s mother, a situation that slowly spirals out of control. May detests Ruby, and after he and Ruth have a baby boy, May belittles Ruby, sabotaging his relationship with his wife and son. May’s, Ruth’s, and Ruby’s relationships are beset by verbal abuse, violent outbursts, drinking, and addiction to pills, personifying the weariness of poverty, grief, and broken dreams.

I loved this book. It’s a sad tale, like a Biblical tragedy. But Hamilton’s beautiful writing, universal themes, and captivating story carry readers through to the end.

In 1988, Hamilton’s novel won the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for best first novel. In 1995, it was an Oprah’s Book Club selection.

We’ll Prescribe You a Cat by Syou Ishida is a warm-hearted novel with a touch of magical realism.

In a group of loosely connected stories, a series of frustrated, anxiety-ridden characters driven by desperation seek help from a mysterious clinic. Some of the characters are deeply distressed about their jobs, others have strained relationships with their families. Some of the characters have trouble at work and home. The clinic is nearly impossible to find, but when they do locate it, they expect to meet a traditional doctor who will provide therapy and dispense medicine to alleviate their symptoms. Instead, they are shocked when the doctor prescribes a cat for a specific length of time, along with instructions for how to care and use their particular cat. To begin with, each of the characters are reluctant to take their cat home, then fail to use their “medicine” as prescribed, causing “side effects” and follow-up visits to the mysterious clinic.

I loved this book because it’s sweet without being saccharine. It avoids predictability, providing twists that I didn’t see coming, and not everything is tied up with a neat little bow. It has touches of humor unique to having been prescribed a cat for what ails one. It was fun to meet the different cats, who all have their own personalities.

We’ll Prescribe You a Cat was a bestseller in Japan, and it has been translated into over two dozen languages.

Rescuing Claire, a novel by Thomas Johnson, transports readers back to college life in the early 1970s, to the days of free love, drugs, the Vietnam War, campus protests, civil rights movements, women’s rights. Johnson nails the chaotic vibe that rippled through college campuses. I was twelve or thirteen years old at the time this novel takes place, old enough to have impressions and memories of the turbulent years of the counter-culture and social revolution, but too young to have participated.

Henry Fitzgerald lives and works in Northern Wisconsin, where he co-owns a lodge with an older couple. His days at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are behind him. But on a crisp autumn day, he receives two letters, one from his wife Elizabeth “Airy” Fitzgerald and one from his former college girlfriend Claire Cohen. Henry gives little thought to his wife’s words, but he takes issue with Claire’s letter. It’s been six years since he’s seen Claire. Her letter is friendly and upbeat as she reminisces about their past, but Henry disagrees with her version of their romance. So he takes a step back in time and tells us his story.

Henry is engaged to Airy, an archaeologist, who is often away on a dig somewhere in the world. He falls for Claire, a coed, who has an arrogant boyfriend named Nicky Waller. Henry’s brother, Milton, an attorney in Madison who champions the legal rights of economically and politically disenfranchised people, warns him to steer clear of Claire. Eventually, Claire goes to work for Leonard Lent, a slimebag. Henry decides he must rescue Claire from Leonard’s clutches, so he forms a dangerous liaison with Norman O’Keefe who wants to kill Leonard. Artfully developed, the supporting cast of characters come to life in the book.

Henry isn’t the most reliable narrator, and perhaps he doesn’t outright lie, but he has a skewed view of the facts. He doesn’t always come off well in the telling of his story because he is forthcoming about his faults and honest about some of the stupid stuff he does. He is likable, infuriating, astute, witty, and annoying in turns. But he is never dull.

One of the best things about this book is the first-person narration — I never tired of listening to Henry tell his story.

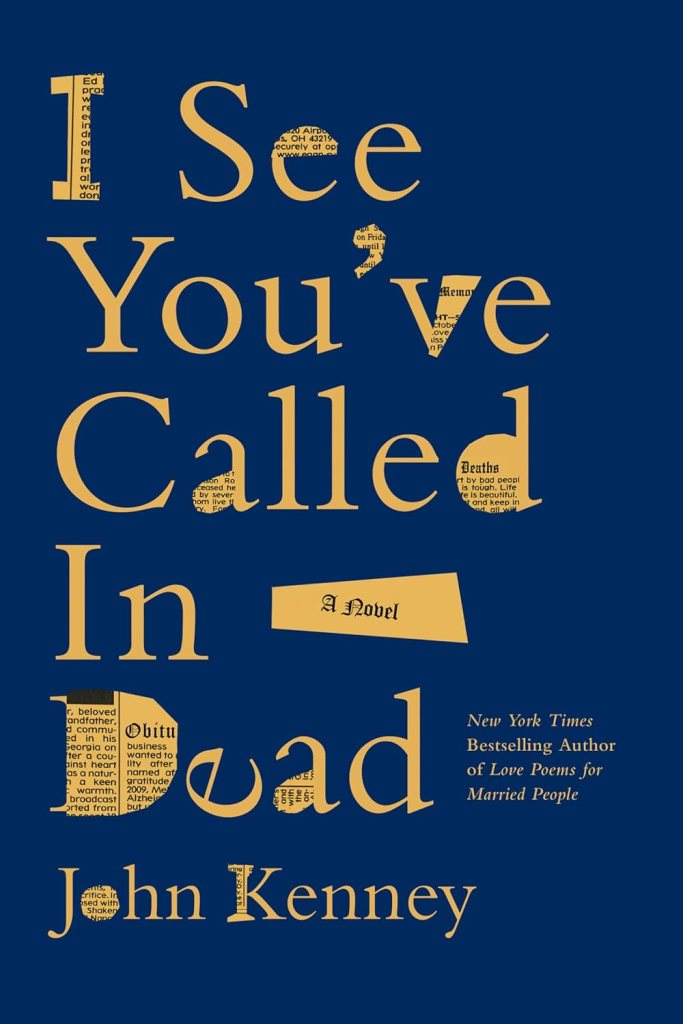

I See You’ve Called in Dead, a novel by John Kenney, is a funny, bittersweet coming of middle-age story that explores themes of male friendships, life’s disappointments, starting over, and mortality.

Buddy Stanley has reached his early 40s, and life isn’t going his way. He writes obituaries for a newspaper, a job he once liked but now sees as a sign of failure. It’s the kind of newspaper job up-and-coming journalists might cut their teeth on, but not one they want in perpetuity. Buddy’s marriage ended in divorce two years ago. His ex-wife has moved on with a tall, sophisticated British man, but Buddy has parked his life in a stall of melancholy and regret. Hoping to help him out, one of his friends sets him up on a blind date. When his date finally arrives, it’s to let him know she and her former boyfriend are getting back together. Depressed about his life, Buddy goes home. After a few too many whiskeys, he decides it would be fun to log into his work account and write his own obituary. After having his bit of hilarity, he reaches to delete his fabricated obituary, but in his tipsy state, things go awry, and he accidentally, irretrievably publishes his obituary online. His best friend Tim is concerned about him. His co-worker Tuan is angry and worried at the same time. Howard, his long-time boss and friend, is disappointed. He knows he’ll have to fire Buddy, even though he doesn’t want to. Howard’s bosses and the head of HR are incensed by Buddy’s flagrant disregard for company rules.

I loved this book because as I followed Buddy through his existential death and eventual “rebirth,” I laughed, and cried, and cheered. I also loved the New York-ness of this novel, a place where quirky people do off-beat things and converse in the language of sarcasm.

I See You Called in Dead was an NPR 2025 “Books We Love” selection, a USA Today April Pick, and a 2026 Gotham Book Prize Finalist (winner to be announced March 31, 2026). John Kenney won a Thurber Prize for his novel Truth in Advertising.