Nellie (my granddog): I heard you suggested taking me through the carwash.

Me: I’d thought about it.

Nellie: Well, let me tell you, I don’t even like windshield wiper blades.

Nellie (my granddog): I heard you suggested taking me through the carwash.

Me: I’d thought about it.

Nellie: Well, let me tell you, I don’t even like windshield wiper blades.

When the busy day is done, all the walks and treats and belly rubs, find your furry buddy and close your eyes. And dream your doggie dreams.

Dreams of fast runs, forest paths, green fields, chattering squirrels, hopping rabbits, and chittering birds.

Ziva was born in Barrett, Minnesota, on a rolling farm, but has lived her life in Wisconsin at the tip of Lake Superior. Her father’s name was Rufus and her mother’s name was Ziva. So, yes, Ziva is named after her mother, but she is also named after Ziva David from the TV show NCIS. I think the Ziva David character is very kick-ass with a great sense of humor. Our Ziva, however, is a forty-six-pound baby, who has more in common with the Cowardly Lion. But our Ziva does make us laugh. Her full name is Ziva Baby, and it suits her

If I show you a picture of Ziva, you will probably think she is a black poodle. But, we’re not so sure. When Ziva was three-and-a-half months old, two different poodle breeders told me she was actually a blue poodle. “What’s that?” people sometimes ask. In Travels with Charley, John Steinbeck describes his blue standard poodle, Charley, by saying that he looks like a dirty black poodle who needs a bath.

When she was three months old, I enrolled Ziva in a puppy socialization class. She had mixed feelings about the course. She was okay with the part where she got to sit on my lap while the dog trainer answered questions. And she didn’t mind being passed around from human to human. But when it was time to mingle with the other puppies, she crawled under the bench and hid behind my legs. Finally, the dog trainer placed us with a group of designer micro dogs, figuring the teeny-tiny pups wouldn’t be as scary. Ziva still crawled behind my legs. When she finished puppy socialization class, she was given a certificate of completion. Purely a feel-good thing because she was too shy to socialize with the other puppies.

Riding high on Ziva’s lack of success in the puppy class, I enrolled her in an obedience class. She loved it. No one expected her to play with the other dogs. She excelled, and after two sessions, she was clearly the teacher’s pet. Me, not so much. Turns out it was not your traditional sit-stay-come-heel class. I had unknowingly enrolled Ziva in a class that was for people who wanted to compete in dog shows or obedience trials with their canines. Ziva learned so quickly that the dog trainers used her to demonstrate different walking moves and turns. The problem? When I had to perform with Ziva, I was all left feet, with no sense of rhythm. Ziva got praise, I got scolded. We only went back to the class a third time because I had to return a collar I had borrowed. After we dropped off the collar, I told the instructor I had to take Ziva out to go potty. But we got back in the car, and feeling like that adolescent girl who couldn’t make the pom squad, I cried. Ziva licked my chin, and crawled onto my lap. We became dog school dropouts.

For years Ziva was a reader — books, magazines, and newspapers. She loved to chew on the written word. I still have the copy of All Quiet on the Western Front that we both savored, except I wasn’t the one who left teeth marks on it. I learned to walk around the house and make sure every book and magazine was put where she couldn’t reach it. But her desire to read triumphed, and she became resourceful. She put her paws on tables and scooped up books. She threaded her face between two couches set at a right angle and slipped my quilting magazines off the bottom shelf of the end table. She poked her snout between the chairs at my desk (placed to keep her out) and selected books off the ledge under the desk. When I successfully blocked these accesses to my books and magazines, she started reading boxes of tissues. So, I left old newspapers on the coffee table in case she wanted to read. About once or twice a month, I’d return home to find shredded newsprint all over the floor. These days she seems to be over her urge to “read.” Perhaps she has become farsighted.

If her sister, Cabela, had a toy she wanted, Ziva would run to the back door and pretend she wanted to go outside. Cabela loved to play outside, so she would drop her toy and run to the door too. My husband or I would open the door. But as soon as Cabela was outside, Ziva turned around and grabbed the toy Cabela had dropped. Cabela is gone now, but Ziva uses this technique on my husband and me. She stands by the back door and pretends she wants to go outside, when we open the door, she does a half turn and stands in front of the microwave, looking up at her bowl of treats. We laugh at her and turn away. But she will do it again and again because she occasionally gets the treat.

Ziva loves to go for rides. She knows when it’s Sunday morning because that is grocery shopping day. She loves to hear “Want to go to the bank?” because she can withdraw treats. When we get the suitcases out, she knows we are going to Michigan. Sometimes Ziva gets carsick, so we keep old towels and blankets on the van floor, and on long trips we give her Dramamine. She is a true road warrior.

And a kind, loving dog.

Ziva is ready for the big game between the Buffalo Bills and the Kansas City Chiefs. She believes she has the best seat in the house. It’s a bed sized for an Irish Wolfhound or a Great Dane. She has room for a companion on this bed, but she would object to another dog sharing it. However, she would share her oversized cushion with my seven-year-old grandson, who snuggles with her on the couch. He has already tried out the bed and declared it “very cozy!”

And no, Ziva doesn’t think it’s necessary to watch the action. She will just listen to Tony Romo and Jim Nantz call the game. She doesn’t care about the temperature and wind conditions on the field. She doesn’t care who wins. But she likes that Taylor Swift is there cheering on her beau. And by the way, so does my eighty-three-year-old mother, who went to see Swift’s Eras Tour in the theater and loved it. After all, “Girls just wanna have fun, that’s all they really want.”

And a cushion fit for a pop star.

“We’ve had this conversation before,” Ziva says. She is smaller than Bogey, four years older than Bogey, and a guest in his house. And he could easily knock her to the floor. But none of that stops her from putting her four paws down when he tries to play with a toy at night.

“Don’t touch that ball. Definitely, don’t squeak that ball,” Ziva says. “I tell you this every time I come to visit.” And she does. For the last eight years or so, Ziva has accompanied my husband and me to Petoskey, Michigan, whenever we visit my mother.

A moment before this photo was snapped, Bogey asked my mother to open the closet door. (If you look to the right in the photo, you can see his box of toys in the closet.) His yellow duck rested on the top, but Bogey selected the white ball because it has a delicious squeak, and because my mother will toss it in the living room for him. This is his nightly routine when we aren’t visiting Mom, and he sees no reason to give it up just because there’s company.

This bothers Ziva. And it bothers me too. Everyone has settled in on a couch or a chair. The humans are talking and watching TV. It’s hard to hear anything over the noise of Bogey’s squealing ball and stomping feet.

Tonight, Ziva rebukes Bogey as soon as she hears the first shriek from the ball. She springs from the couch where a second ago she seemed to be in a deep sleep and barks as she approaches him. Bogey drops the ball before she reaches him.

“Go ahead. I double dare you!” Ziva says, watching Bogey while she looks askance at the ball. They stand close together, frozen, for at least a minute. She doesn’t make a move for the ball because she doesn’t want it. She never wants his toys. At eight o’clock at night, she wants peace and quiet. Bogey has turned his head away, and refuses to make eye contact. He waits for her to go away, but she doesn’t. Not another word passes between them. Like a pair of disgruntled lovers, they’ve had this conversation so many times over the years that it has now become a wordless exchange, each side knowing what the other side would say if they did speak.

Ziva refuses to retreat. Finally, Bogey gives up and leaves the ball. He crawls under the long skinny table behind his favorite couch and sulks and waits. Ziva returns to her favorite couch.

Ten minutes later Bogey emerges from under the table and silently shuffles to the closet. He roots through his box of toys and pulls out a multi-colored stuffed caterpillar. He slinks into the den with his toy. He knows if he enters the living room with it, he won’t be allowed to have it. The ball Bogey had wanted to play with still lays on the living room floor. If Ziva heard him, she ignored him, allowing him a small victory.

Even tucked out of sight in the den, Bogey knows not to make the caterpillar squeal. He’s a very smart dog, and he has never won this argument.

Today while I was writing, Ziva, my twelve-year-old standard poodle, slept on her dog bed in my office. She doesn’t take my writing seriously. She takes a nap. And when she is bored with napping, she will get up and jab my right elbow with her nose. This means she wants a walk, because when we return she knows she will get a treat. She’s very good with cause and effect. If I ignore her first jab, she will jab again and again, until I say, “Okay, just let me finish this sentence.” It’s difficult to type when my elbow is suddenly tossed into the air by Ziva’s snout. But, today we walked before I started writing, so she was content to sleep instead of interrupting my stuttering flow of creative whatever.

Today’s big distraction took place outside my office window. Nuthatches, chickadees, house finches, a downy woodpecker, and a squirrel showed up at the bird feeder that hangs in the pine tree. It was a comic opera of dance, birdsongs, and slapstick.

The nuthatches and chickadees were happy to take turns at the feeder, but when a pair of house finches arrived, the other birds backed off and lit upon nearby branches in the pine tree. The house finches parked themselves on the feeder and ate, and ate. House finches are about the same size as the nuthatches and chickadees, but they obviously have an unsavory reputation in their small-bird community.

Occasionally, a chickadee attempted to fly in and snitch a seed, but the finches refused to yield. The chickadee, chickening out at the last second, would furiously flap its wings, nearly come to a screeching halt, then hover a moment before veering off to the left or right, returning to a branch in the tree. One chickadee flew up to the feeder, and one of the house finches turned its head, making a motion like a dog barking to defend its dish of food. The chickadee made a hasty retreat.

For the most part, the nuthatches made do with eating insects they found on the bark of the pine tree. But occasionally, one of them, craving a tasty sunflower seed, bravely approached the feeder. The house finches weren’t intimidated by them either.

During all this comedic drama, a squirrel arrived. His fluffed-out, bad-ass, tail-twitching demeanor made all the birds, including the house finches, seek higher branches. I chuckled because my bird feeder is squirrel proof. Many squirrels have tried, and all have failed. In a scene of choreographed comedic buffoonery, I watched the squirrel walk back and forth on the branch, eyeing the feeder. Next, he climbed on top of the feeder and stretched a paw downward toward the opening filled with sunflower seeds. Maybe, I thought, this one will figure out how to nab a seed from the squirrel-proof feeder. But no. He was only providing that moment in a story when we think a character will get what she wants, which made the next moment funnier because the squirrel fell off the feeder and onto the ground. My laughter startled Ziva, who lifted her head. The birds, however, wasted no time guffawing. They vied for position at the feeder.

And the squirrel was fine. He climbed back up the tree and sat a couple of branches above the feeder. He made a big show of licking his paws then smoothing the fur around his face and ears. Finally, he fluffed his tail with his tiny claws then gave it a swish, swish through the air. His rendition of a human tripping, picking herself up, looking around to see if anyone saw her fall, then smoothing out her clothes, before moving along like nothing happened. The squirrel made no second attempt at the feeder. The house finches came and went a few times, and each time they departed the chickadees and nuthatches rejoiced.

A downy woodpecker joined the troupe, an extra without a speaking role, relegating herself to the background while she pecked at the branches and trunk of the pine tree. Downy woodpeckers like to chum with chickadees and nuthatches, maybe because they take turns at the feeder, and downy woodpeckers like sunflower seeds. But today she was above jostling for seed, maybe she didn’t like house finches either.

I was supposed to be writing, but all the drama at the bird feeder was as good as a rousing, twisting, turning period drama on Masterpiece Theatre. Cooperation, backstabbing, greed, ingenuity, snobbery, high drama, and comic relief all outside my window. All potential themes and plot twists for a future story I might write.

And I managed to write a blog piece about it.

Cabela died at 11:30 on the night of August 4. She was fifteen years old, and we loved her very much. She was a brown standard poodle born on June 24, 2008, in a red barn on a farm in Barret, Minnesota. Her first human parents were Emmet and Ruth, a pair of kind farmers who raised Labradors and standard poodles for pin money. Cabela spent her early puppy days playing outside on their farm with her siblings in the summer sunshine. She developed a life-long love of being outdoors.

When we brought Cabela home, she wanted to be outside all the time. She liked to sit or lay under my husband’s maple tree in the front yard. She believed her job was to patrol the yard, watching cars and pedestrians move up and down the streets at the front and the side of our house. She and the priest who lived across the street became friends. When he left or returned home in his silver Buick, he would slow to a crawl to see if Cabela was outside. If she was, she would line up with his car, he on the road and she in our yard. The priest would slowly accelerate and Cabela would accelerate. They raced until she reached our lot line. The priest always ended the race in a tie, and the two of them enjoyed their game for years. In her prime when Cabela was excited, she ran hot laps, up to six or seven of them in a row, around our yard at warp speed, or she launched herself six feet into the air along the trunk of a tall pine tree. Drivers would stop and watch her performance. Dr. Jenny, her regular vet, once remarked, “Cabela has the heartrate of an athlete.” I said, “She is an athlete.”

Cabela died because her stomach twisted. The medical term for this is Gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV). It’s more common in deep-chested dogs like standard poodles, and it’s more problematic in older dogs because the muscles and ligaments holding their stomachs in place become weak and more elastic. The emergency hospital vet, Dr. H, asked me if Cabela was spayed and when I said yes, he asked if her stomach had been tacked at the time. I’d never heard of this, but it’s supposed to help prevent GDV. I have no idea if Cabela’s stomach was tacked when she was fixed.

On August 4, Cabela’s evening started out normal. She ate her supper, and an hour later she went for a walk with her sister, Ziva, and me. Cabela still loved her walks, but they were now a slow, grass-sniffing shuffle around the block, then she was done. After the walk she rambled around the house. This too was part of her evening routine. She had a touch of dementia, which often became more noticeable in the evening. In humans with dementia, this is called sundowning. Cabala would look like a person who had entered a room but couldn’t remember why, no matter how hard she tried. Usually after thirty to sixty minutes of intermittent ramblings, she settled into a deep peaceful sleep until the wee hours of the morning when she would wake me up so she could go outside and potty.

But on that night, Cabela wouldn’t even lay down for a short rest. She moved from the family room to the living room and back again. My husband and I encouraged her to lay down. We stroked her head and ears when she came near us. We patted the couch cushion, inviting her to hop up and rest. But she backed away and kept moving. We wondered if her hips or legs were in pain. She was arthritic and her hind leg muscles had begun to atrophy. We wondered if she’d torn a ligament. She didn’t cry or whine or wince. Cabela was so very stoic all her life, and at the end of her life she would be no different. Later that night while treating her, Dr. H would remark, “Cabela is one of the most stoic dogs I’ve ever treated.”

At nine o’clock, I gently helped Cabela lay down on her sheepskin bed. She resisted for a moment, then relaxed. She closed her eyes, and I stroked her face and neck. She fell asleep. Later I would realize that for a few minutes either fatigue got the best of her pain or the position in which she lay gave her a brief respite from it. But at that moment, it appeared she would sleep until the wee hours of the morning. I sat with her for five minutes, watching the peaceful rise and fall of her chest, her only movement. Then I let her be and returned to the family room.

But a few minutes later Cabela was up and walking around, lost and confused, looking at me with sad eyes. I tried to lay her down again and soothe her, but she was having none of it. She snapped at me, placing her teeth gently on my arm. She kept pacing. At ten o’clock I took Cabela to the animal hospital.

I had to carry her into the van. Again she whipped her head around and nipped at me. This time her head banged into my glasses, bending my wire-rim frames. She rested her teeth on my shoulder, but did not bite down. Only later would I understand she was saying, “It hurts so bad.”

We arrived at the hospital, and I had to lift Cabela out of the van. She snapped at me one last time, still all warning and no bite. After I described her symptoms to the receptionist, Cabela was seen immediately. Dr. H and the techs were wonderful to Cabela and me. The vet suspected her stomach had twisted. I felt awful. I told the doctor that I thought she had been sundowning. He understood because he’d had a beagle who had episodes of sundowning as an old dog. He remarked that Cabela had a very good heart rate for a dog her age. “She was an athlete,” I said.

Cabela was taken back into the hospital where she was sedated to relieve her pain, then she had her abdomen x-rayed. I knew if her stomach was twisted, she would need to be put to sleep. Dogs do have surgery to correct twisted stomachs and often survive if the condition is caught early. But Cabela was fifteen years old with some dementia, nearly deaf, arthritic with weak muscles, and during her initial exam, Dr. H had discovered she was nearly blind in her right eye.

Cabela’s x-ray confirmed that her stomach had twisted. The vet said because I’d brought her in so quickly, she would’ve been a good candidate for surgery if she had been younger and in good health. “But to do this surgery on her at this stage of her life,” he said, “would be cruel.” And I agreed. The vet left to get the medicine needed to put Cabela to sleep.

The tech brought Cabela back to me and I sat on the floor and held her. She was heavily sedated, breathing quietly, soft and warm in my lap. I asked the tech if he had a pair of scissors so I could have a snippet of Cabela’s hair as a keepsake. He kindly made this happen. Then the vet returned. After Cabela died, I was given time alone with her. I held her. I thanked her for being such a good dog. I told her she would see her old pal Bailey, our first standard poodle, and they could play and nothing would hurt. They loved to chase one another and play tuggy with an elastic-filled, furry toy we called Lizzy. Bailey died when Cabela was two and a half, and she looked for Bailey for weeks. When my husband and I brought Cabela home and introduced the two of them, they began to play immediately. Every minute or so, Bailey would run back to my husband or me, wagging her tail and smiling as if to say, “Thank you! Thank you so much for bringing me a puppy!” Then she would dash back to play with Cabela.

We met Cabela on a pleasant September day in 2008 in Owatonna, Minnesota, near the Cabela’s sporting goods store, for which she would be named. My husband and I and my youngest son and his future wife were eating lunch in a restaurant and watching out the window as people walked up and down a row of dog breeders who had set up along a wide grassy boulevard. The breeders came from Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Minnesota to sell leftover puppies they hadn’t been able to sell back home. We decided after lunch to look at them. I thought about free puppy cuddles. We already had our two-year-old standard poodle, Bailey, so I had no interest in getting another dog.

The four of us visited the standard poodle puppies first, and my son scooped up a chocolate one and snuggled her to his chest. Content, the puppy nuzzled in and closed her eyes. I talked to the woman about her poodles and my poodle. And while I talked, my son whispered, “Take her home, please, just take her home.” He repeated the words over and over. I looked at my eighteen-year-old son, holding this puppy, and my heart melted. I asked the lady how much she wanted for the puppy. Her answer was reasonable. I asked my husband if it was okay with him, and without hesitation he said it was. I wrote the woman a check, and my son carried her to the car. We never visited the other breeds of puppies.

We named our new puppy in record time. Because she was a chocolate-colored dog, my husband suggested Hershey, which I immediately nixed. “That name will encourage jokes about the Hershey squirts.” My husband laughed, but this was an indignity I felt no dog should have to endure. My son suggested Cabela, and we all agreed it was a great name. Cabela was eleven weeks old when we bought her, and I am eternally grateful that no one else had chosen her. She earned her middle name when during a case of the zoomies, she misjudged the width of the hallway and ran head first into a wall. As she shook her head, I said, “Your middle name is now Grace.” Over the years we gave her lots of nicknames: The Brown Bomber, Range Rover, Ichabod, Snickerdoodle, Kadiddlehopper, and Bel. I once read somewhere that a well-loved pet will have many nicknames.

It was after midnight when I came home without Cabela. I came in through the garage and up the basement stairs. Ziva stood at the top of the steps, waiting. She kept looking to either side of me, watching for Cabela to come up the stairs. Even though it was late, I knew I wouldn’t sleep, so I sat on the loveseat and Ziva climbed up on her favorite couch. I turned on the TV, but I have know idea what I watched. Every now and then, Ziva heard a noise and her head popped up. She looked toward the hallway, waiting to see Cabela come into the family room.

In 2011, after Bailey had died, Cabela was lonely. She had liked having a dog buddy, so we called Emmet and Ruth. Luckily one of their poodles had recently had puppies, so we reserved one for Cabela. But, when we brought Ziva home, she didn’t want to play with Cabela. Every time Cabela came near her, Ziva squealed like she was in mortal danger. And each time Cabela moved away and gave her space. “Won’t that be something if Ziva never wants to play?” my husband and I would say. Thankfully, two weeks later, Ziva approached Cabela and said, “Let’s play.” And they, too, became buddies.

Cabela died on a Friday night, and that weekend I couldn’t stay in the house. I wanted to be outside where Cabela had loved to be. I felt her spirit would be in the yard. I spent the whole weekend outside, making things look pretty for Cabela. I weeded gardens and picked up sticks. My husband helped me wash windows, clean gutters, and dig up some scraggly, out-of-control bushes so we could plant new ones next spring. If I mentioned Cabela’s name and Ziva heard me, she looked at me quickly and intently and cocked her head. “Where?” she would ask. She seemed so sad, too.

I miss Cabela. I loved how her ears flapped in the wind when she sat in our front yard on breezy days. I miss how she poodle-pranced down the street on our walks. I miss how she could raise one eyebrow and then the next, alternating back and forth when she asked for a treat. I miss seeing her on the living room couch, her front paws resting on its back and her head resting on her paws as she looked out the window, working the yard from inside the house. I miss how she would turn to look at us each night before she headed down the hall to her sheepskin bed. “Calling it a night?” my husband would ask, then say, “Have a good sleep.”

[My dog Cabela died two months ago. I’ve tried to blog about her dying (because I blogged about her when she was living) but I would end up crying. Then I would decide my words were fluff, unable to capture her essence and the hole left in my heart by her death. A couple of days ago I read “When a Cold Nose is at the Pearly Gates: Writing a Pet’s Obituary” by Laurel E. Hunt on Brevity Blog. After I finished reading Hunt’s blog, I tried writing about Cabela’s death in the form of an obituary, but that didn’t work for me either. And I cried again. Even thought Hunt’s writing idea didn’t work for me, I’m thankful I read her blog on October 6 because she inspired me to try and write about Cabela again. To learn more about GDV click here.]

[I’ve read many good books in the past few months. I’m going to review some of them in a series of blog posts. So, if you’re looking for a summer read, maybe you’ll find a book to enjoy in one of my book review posts.]

Why did I read this book?

I bought Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend in 2011 after listening to an interview of Susan Orlean on Minnesota Public Radio. (Click on the blue font to hear her talk about the book. She gives a good interview.)

I’d never seen a Rin Tin Tin movie or TV show, but I’d heard of the famous Rin Tin Tin because he was often referenced in popular culture. Rin Tin Tin’s story appealed to me for two reasons. One, I like reading about the movie industry, especially the history of its beginnings. And two, I grew up with a German Shepherd named Fritz, who was intelligent and kind, and at times heroic. Our Fritz could’ve been the Rin Tin Tin of the silver screen.

Sad to say it took twelve years before I lifted the book off my to-be-read pile of books. Sad because Susan Orlean’s book is a fascinating combination of three stories.

What is this book about?

It’s the story of a man and his love for an extraordinary dog. Orlean’s book follows the life of Lee Duncan who rescues Rin Tin Tin, a German Shepherd puppy, from a bombed out kennel in France during WWI. In a way Rin Tin Tin rescues Duncan, too, because Duncan, who had a tough childhood, is a wounded soul. Duncan brings Rinty, as the dog was sometimes called, home to America. With Duncan’s care and training, Rin Tin Tin becomes a Hollywood superstar during the silent film era. After Rin Tin Tin dies, Duncan continues to work with other German Shepherds who acted in movies and the television show The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin.

It’s the story of canine and human actors; animal trainers; and Hollywood executives and producers; many of whom become famous and rich (and sometimes bankrupt then rich again then broke again) during the early days of Hollywood and television. Orlean delves into the behind-the-scenes pitches, ideas, deals, and strategies that created and promoted the Rin Tin Tin movies, TV shows, and actors.

It’s the story of Orlean’s fascination, research, and commitment to the story of Rin Tin Tin. She is old enough to remember watching the TV show The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin with her older siblings and loving Rin Tin Tin. But she was only four years old during the last season of the show and remembers nothing about the show itself. She writes about the fascination she and her siblings had with a small Rin Tin Tin toy her grandfather kept on his desk, out of their reach. She remembers the day when, while researching another story, she came across the name Rin Tin Tin, which brought back a flood of memories and emotions about the famous German Shepherd from her childhood. In her book Orlean writes about why she wrote this book, how she did the research, and how the book changed her.

What makes this book memorable?

Orlean is an outstanding journalist, which shows in her dedication to research and her passion for accuracy. Hollywood moguls, however, are in the business of creating legends, and they often spin legendary stories, which light up our imaginations but may have little or no truth to them. Orlean worked to track down the veracity of the many stories that had been handed down about the people and animals in her book. When she can’t find facts to either corroborate or refute a story, she lets readers know. As a reader, I appreciate Orlean’s extra effort to get at the truth, rather than repeating information that may not be true.

It took Orlean ten years to research and write Rin Tin Tin. She was granted access to the vast collection of documents saved by Lee Duncan and other people featured in the story. She interviewed as many people as she could who were connected to the story of Duncan and Rinty. Some of her research included traveling to the places she wrote about, like movie and TV locations where Rin Tin Tin films were shot, and Paris where Rin Tin Tin is supposedly buried in an elegant, verdant pet cemetery.

When Orlean writes about people in her books, she does so in a fair and balanced way, making them neither heroes nor villains. This is something about Orlean’s writing I came to appreciate when I read The Library Book (2018). [I read this nonfiction book a couple of years ago. It would make another excellent summer read.]

Orlean’s artful weaving of the stories of Duncan and Rinty, the early days of Hollywood, and her journey to uncover the mystique of Rin Tin Tin makes for an engaging narrative.

[Link to the silent film Clash of the Wolves starring Rin Tin Tin. Link to full-length movie The Return of Rin Tin Tin (1947) with Robert Blake. Episodes of The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin can be found on YouTube, also.]

The dog’s water dish has gone missing. My husband has looked everywhere for it, and he announces he can’t find it anywhere.

I’m reading, trying to finish a book before we need to pick up his father and take him out to eat.

Not being able to find the stainless-steel water dish with a nonskid rubber bottom has flummoxed my spouse. He says, “This is bizarre.”

Not to me: In my world things have always occasionally gone missing, but most of the time the objects have returned. I’ve learned to take a deep breath, stop looking for the missing item, and trust it will reappear when it’s ready.

Over twenty years ago, I lost my purse. I searched the house and the car but couldn’t find it. I decided I must have forgotten it at work. I drove back to work and searched for my purse. I asked if anyone had turned it in. No luck. I returned home and cancelled my credit cards, which was the easy part. Going to the DMV to replace my driver’s license would have been a joyless, time-consuming task. I needed to cook supper, so I went into my bedroom to change out of my dress clothes. I shut the door behind me and there, hanging on the hook on the back of the door, was my purse. At that moment I remembered having hung it on the hook, a place I’d never before put my purse.

For years I played where-in-the-Sam-Hill-are-my-car-keys with myself. I’d come into the house with groceries or kids or both. The keys in my hand would get stuffed in a pocket or laid on a random surface somewhere in the house. A few hours later or the next day, the hunt for the keys would begin. After one particularly stressful search, I made a hard-and-fast rule for myself: I must either hang the keys on the hook in the hallway or put them in my purse. It’s been years since I’ve done a frantic search for my car keys.

My husband continues his search. I try to ignore the lost-water-dish ruckus. The book I’m reading is very good. Besides, I believe the dish will turn up, but only if he stops looking for it.

He wonders if someone stole it. I doubt someone would come onto our deck and take a dog’s water dish. Then for a moment, I think maybe a fox took it, which is even more preposterous, but more amusing to contemplate. I keep reading (the book is very good). He keeps searching and grumbling.

I try to ignore him because I know the dish will show up somewhere. Years of experience has taught me this. And when I find a lost object, I remember having put it there — but only after I’ve found it. However, this time I’m certain I’m not to blame for the missing item. And to my husband’s credit, he doesn’t ask me if I’ve done something with it. (Which would be a valid question, and I know it.)

The book is so good, and I’m reaching the end, a very interesting and poignant climax. But I realize I’m not going to enjoy the ending without interruption, so I get up and join the search party.

I look in the same places he has looked: the counter, the floor, the dishwasher. Then I go out on the deck and look at the dog’s tray. No water dish. I don’t know what makes me do it, but I walk about ten feet to the edge of the deck. Next to two plants waiting to be put into the ground is the dog’s water dish. Only then do I remember.

I pick up the dish and go back into the house. “I found it,” I say. “It was by the plants at the edge of the deck.”

“How did it get there?”

Not wanting to waste water, I used the old water in the dish to give the plants a drink. I don’t know why I set it next to the plants (which I’ve never done before) instead of refilling it and returning it to the tray. I must have been distracted, probably by one of the dogs in the yard.

“I have no idea,” I say. I’ve seen my fair share of spy thrillers and decide the explanation is on a need-to-know basis. Does he really need to know my forgetfulness caused him a few minutes of puzzlement? Not at all.

He doesn’t say anything more, and I imagine he believes Cabela somehow pushed it over there because lately she’s been banging her dishes about a bit with her clumsy feet.

Later, I wonder if my husband really suspects me of having moved the bowl, but to his credit, he doesn’t mention it. (It would be a valid suspicion, and I know it.)

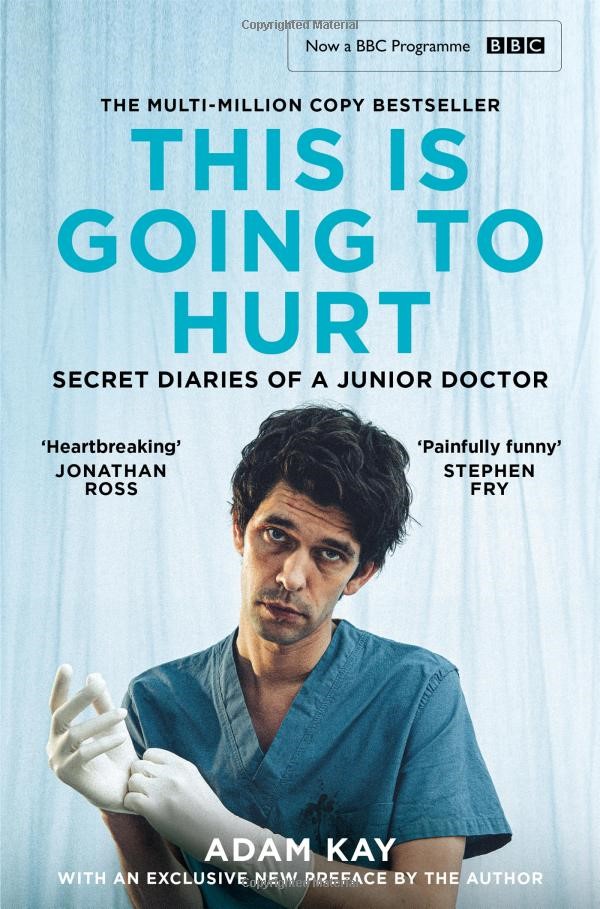

[In case you’re wondering, I was reading This Is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay. The book is nonfiction. Kay tells stories from his years as a doctor, before he quit to pursue a career as a comedian and a writer for TV and movies. Doctors from all over the world have written to tell him that his experiences as a doctor mirror their experiences as doctors. If you’re a doctor, you’ll probably like the book because you’ll appreciate that someone gets you and understands what the job is like. If you’re not a doctor, you should read the book because you’ll gain insight into a profession that we might all assume we understand because we go to doctors, but we really don’t.]

We don’t have any celebrations planned.

Each day that Cabela is still with us and healthy enough to enjoy her food, a walk, and a gallop around the yard is a celebration. However, today she is having a spa day, but she knows “spa day” is just a fancy term for a bath and a haircut. She has always liked her beauty appointments, but last month the groomer told me Cabela balked a bit about being brushed out and clipped, especially around her legs and feet. This didn’t surprise me because Cabela moves slowly these days, with an off-kilter hitch in her giddy-up.

I’m sure Cabela has arthritis. When she is willing to take it, I give her a mild pain medication to help with her aches and pains. Most days she eats the pill like she is The Mrs. Astor nibbling a tasty hors d’oeuvre. Other days she turns her nose up like she is Tom Sawyer forced to swallow cod liver oil. Because she doesn’t need the medicine to survive, I let her decide if she wants to take it or not.

I’m proud of Cabela and her 15th birthday, so over the past several months, I’ve repeatedly said to family and friends, “You know, Cabela is going to be 15 years old on June 24.” This morning I sent texts along with a birthday photo of Cabela to family and friends announcing her milestone birthday. Throughout the day, text messages have come through for her. When my husband and I picked Cabela and her sister, Ziva, up from the groomer this afternoon, I read the texts to her.

According to a chart put out by the American Kennel Club, Cabela is 93 years old. A couple of days ago, my 6-year-old grandson kept asking questions about measuring a dog’s life in human years. I tried to answer each question, but the more I tried to explain it, the more questions he asked, including, “How old are people in dog years?” (He asks a lot of interesting questions.)

I told him there wasn’t a chart for that. But this morning I was still thinking about his question. Using the AKC chart, I came up with a way to answer it. Cabela is a large-breed dog, so I chose that category. I moved down the column of a dog’s age in human years until I reached 61 years. The number below that is 66 years. I’m 64 years old. Next, I moved horizontally to the left on the chart, and I found that in dog years I’m between 9 and 10 years old. That makes sense to me because a large-breed, 9-year-old dog is entering its senior citizen years just like I am.

It still amazes me that Cabela came into our home as an 11-week-old puppy, and she is now older than me. It amazes my grandson too. He wanted to know how Cabela could be considered older than his 64-year-old nana. “Most animals,” I said, “age faster than humans.” Of course, he asked what that meant. I reworded my answer: “They grow old faster than humans.” He was quiet, but I don’t think it was because I had managed to explain the mysterious dynamic of aging in dogs and humans. Most likely he was trying to incorporate the new information with his current understanding of aging.

I printed the “How Old Is My Dog in Human Years?” chart for my grandson, so when he comes back on Monday, he can see a visual of the dog-to-human-years concept. I’m sure he’ll have more questions, and he likes to ask them when we’re in the car.

I have to admit this year Cabela’s birthday makes me sad. At 15 (or 93 in human years) she is doing okay. But if she makes it to her 16th birthday, she will be 99 years old. She will age 6 human years in one dog year. Standard poodles have a life expectancy of 11 to 13 years.

When I took Cabela for a walk around the block this morning, I let her go as slow as she wanted. I let her smell each interesting spot as long as she wanted. Ziva and I waited as if we had nowhere else to go, nowhere else we would rather be, and no one else we would rather be with.

Cabela’s day-spa afternoon was a success. The groomer said Cabela did well today, no signs of discomfort. And she looks marvelous, all soft and fluffy. She also smells frou-frou, like she sampled the wares at a perfume counter.

Cabela is taking a well-deserved nap now. As a dear friend of mine once said, “It’s not easy being eye-candy.”

Happy birthday to Cabela, who is still beautiful inside and out!