Yesterday, after her rough morning, Ziva had a slightly better afternoon. She still slept most of the time, but when she did get up, she moved better, slowly and cautiously, but better.

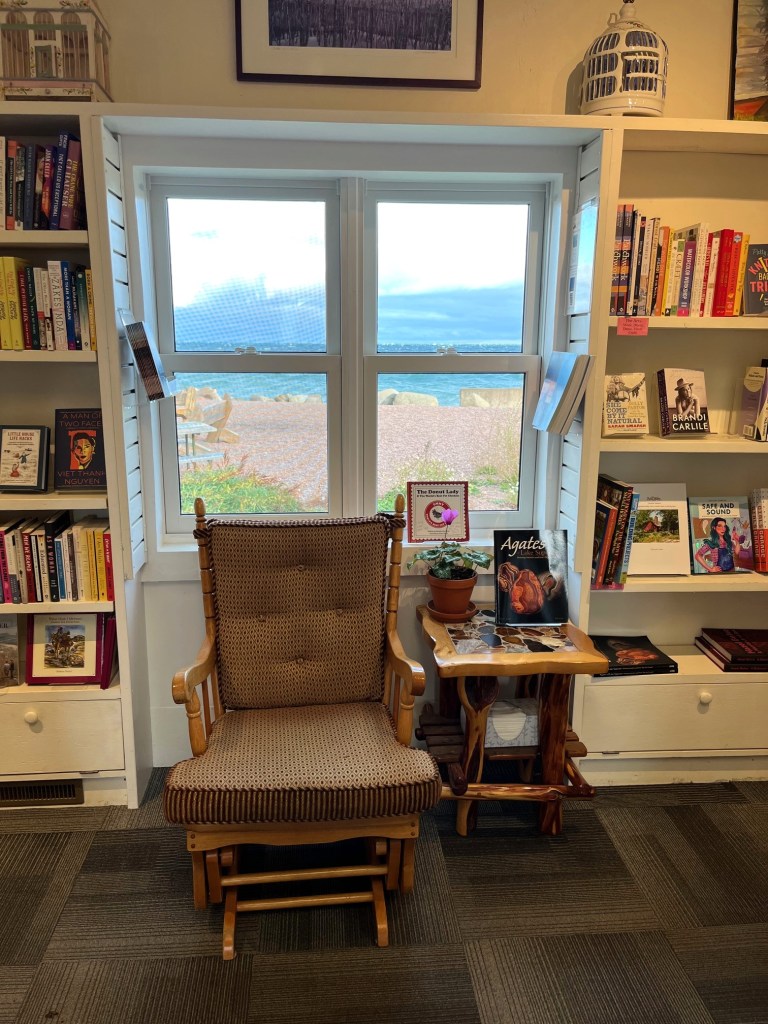

I’ve become an expert at watching Ziva’s movements and her gait. I’ve been doing it for five or six years now. We walk a lot, so I’m able to note how she moves from day to day, week to week, and month to month. In 2017, I read Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Dr. Atul Gawande. He wrote that if doctors know what they are looking at, they can tell a lot about an older person by the way he or she walks. When I worked at a bookstore, medical students sometimes came in with a list of suggested reading (beyond medical texts) given to them by a professor. I always suggested they add Gawande’s Being Mortal to their stack because it deals with aging and death, topics about which they would receive little exposure to in medical school. They usually bought the book because I was able to convince them that geriatric and end-of-life concerns were going to figure in their practice — regardless of their medical specialties. And so, I watch Ziva’s gait and movements. I note the changes over time, and I can describe them to the vet in a manner that impresses her and helps her to treat Ziva. I did the same with Cabela, Ziva’s sister, as she aged.

When my husband and I came home from the grocery store yesterday afternoon, Ziva met us at the door and wagged her tail. I realized how much I take her incessant tail wagging for granted. We made a big fuss over her swirling tail and gave her a treat. It might sound like Ziva gets a lot of treats, and she does. Most days she eats her breakfast and supper too, as long as we doctor it up with good stuff (eggs, boiled chicken, a bit of canned food), what my husband likes to call “frosting.” Ziva isn’t overweight. Rather when we go to the vet’s, I hold my breath and hope she hasn’t lost another half-pound. When she weighs the same as she did the last time, I joyfully exhale.

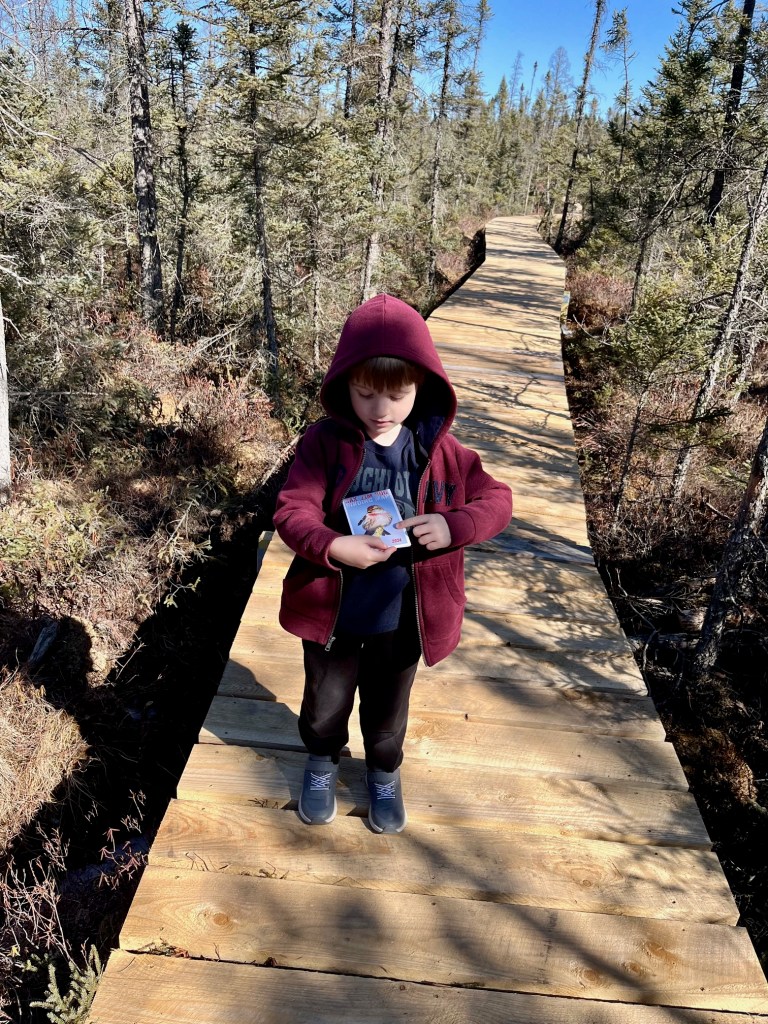

Around three o’clock, while she appeared to be sound asleep, I whispered to my husband that I was going for a walk. Unbeknownst to me, while I got ready, Ziva got up, walked to the back door, and waited for me. (There is nothing wrong with her hearing or her ability to look like she’s in a deep sleep when she’s actually keeping tabs on her people.) She looked at me with big pleading eyes — the ones that say: You’re surely not going without me?

In the morning we’d agreed that Ziva should have lots of rest. No car rides, no walks, no extended outside time. But she stood at the back door, telling she felt better and wanted to walk. I worried she might tweak her injury if she stumbled. But I kept my comments to myself because she didn’t want to hear about my fears. She had her own. And even though she was hurting, she wanted some say in how she was going to get better. In that moment, I weighed her need for a small outing against the chances she might aggravate her injury. I decided her emotional well-being was important to her healing.

When I was nineteen and living with my grandparents, I got very sick. I was on bed rest for two weeks. Finally, I started to feel better. I wanted to do something other than lay in bed. I hadn’t been out of the house since coming home from the hospital, but I was weak. I called my mother, and I started crying as I explained how I felt. She told me to get out of the house for a bit, that if I felt like going out, it was a sign I was getting better. I called my girlfriend, who said that she and her boyfriend were going to a softball game, and they would come and pick me up, take me to the game, then bring me home. My grandmother and I had a big argument about my going out. Of course, she was worried about me. But I didn’t back down. I finally told her, “I called my mother this morning, and she told me I could go out for a bit.” I felt so much better when I returned home a couple of hours later; although, I did need a nap. My grandmother, noting my happy face, said, “It was so nice of your friends to take you out and bring you back.” I believe she was also relieved I hadn’t overdone it.

While I grabbed Ziva’s harness and fastened it around her, I thought about my grandmother and our argument. I explained the rules to Ziva. We would walk down through the grass instead of down the stairs, and our walk would be slow and short. We walked less than one city block, but Ziva went to the bathroom and sniffed a few of her favorite spots along the way. When I announced it was time to go home, she happily turned around. After we got home, she curled up for a big nap, but she had enjoyed herself. After her nap, she wasn’t any worse for the walk, but she didn’t want her after-dinner walk.

This morning Ziva is moving a little faster and with more confidence, but still carefully. And her tail wagging, while not back to normal, tells me her pain has eased a bit.