The dog’s water dish has gone missing. My husband has looked everywhere for it, and he announces he can’t find it anywhere.

I’m reading, trying to finish a book before we need to pick up his father and take him out to eat.

Not being able to find the stainless-steel water dish with a nonskid rubber bottom has flummoxed my spouse. He says, “This is bizarre.”

Not to me: In my world things have always occasionally gone missing, but most of the time the objects have returned. I’ve learned to take a deep breath, stop looking for the missing item, and trust it will reappear when it’s ready.

Over twenty years ago, I lost my purse. I searched the house and the car but couldn’t find it. I decided I must have forgotten it at work. I drove back to work and searched for my purse. I asked if anyone had turned it in. No luck. I returned home and cancelled my credit cards, which was the easy part. Going to the DMV to replace my driver’s license would have been a joyless, time-consuming task. I needed to cook supper, so I went into my bedroom to change out of my dress clothes. I shut the door behind me and there, hanging on the hook on the back of the door, was my purse. At that moment I remembered having hung it on the hook, a place I’d never before put my purse.

For years I played where-in-the-Sam-Hill-are-my-car-keys with myself. I’d come into the house with groceries or kids or both. The keys in my hand would get stuffed in a pocket or laid on a random surface somewhere in the house. A few hours later or the next day, the hunt for the keys would begin. After one particularly stressful search, I made a hard-and-fast rule for myself: I must either hang the keys on the hook in the hallway or put them in my purse. It’s been years since I’ve done a frantic search for my car keys.

My husband continues his search. I try to ignore the lost-water-dish ruckus. The book I’m reading is very good. Besides, I believe the dish will turn up, but only if he stops looking for it.

He wonders if someone stole it. I doubt someone would come onto our deck and take a dog’s water dish. Then for a moment, I think maybe a fox took it, which is even more preposterous, but more amusing to contemplate. I keep reading (the book is very good). He keeps searching and grumbling.

I try to ignore him because I know the dish will show up somewhere. Years of experience has taught me this. And when I find a lost object, I remember having put it there — but only after I’ve found it. However, this time I’m certain I’m not to blame for the missing item. And to my husband’s credit, he doesn’t ask me if I’ve done something with it. (Which would be a valid question, and I know it.)

The book is so good, and I’m reaching the end, a very interesting and poignant climax. But I realize I’m not going to enjoy the ending without interruption, so I get up and join the search party.

I look in the same places he has looked: the counter, the floor, the dishwasher. Then I go out on the deck and look at the dog’s tray. No water dish. I don’t know what makes me do it, but I walk about ten feet to the edge of the deck. Next to two plants waiting to be put into the ground is the dog’s water dish. Only then do I remember.

I pick up the dish and go back into the house. “I found it,” I say. “It was by the plants at the edge of the deck.”

“How did it get there?”

Not wanting to waste water, I used the old water in the dish to give the plants a drink. I don’t know why I set it next to the plants (which I’ve never done before) instead of refilling it and returning it to the tray. I must have been distracted, probably by one of the dogs in the yard.

“I have no idea,” I say. I’ve seen my fair share of spy thrillers and decide the explanation is on a need-to-know basis. Does he really need to know my forgetfulness caused him a few minutes of puzzlement? Not at all.

He doesn’t say anything more, and I imagine he believes Cabela somehow pushed it over there because lately she’s been banging her dishes about a bit with her clumsy feet.

Later, I wonder if my husband really suspects me of having moved the bowl, but to his credit, he doesn’t mention it. (It would be a valid suspicion, and I know it.)

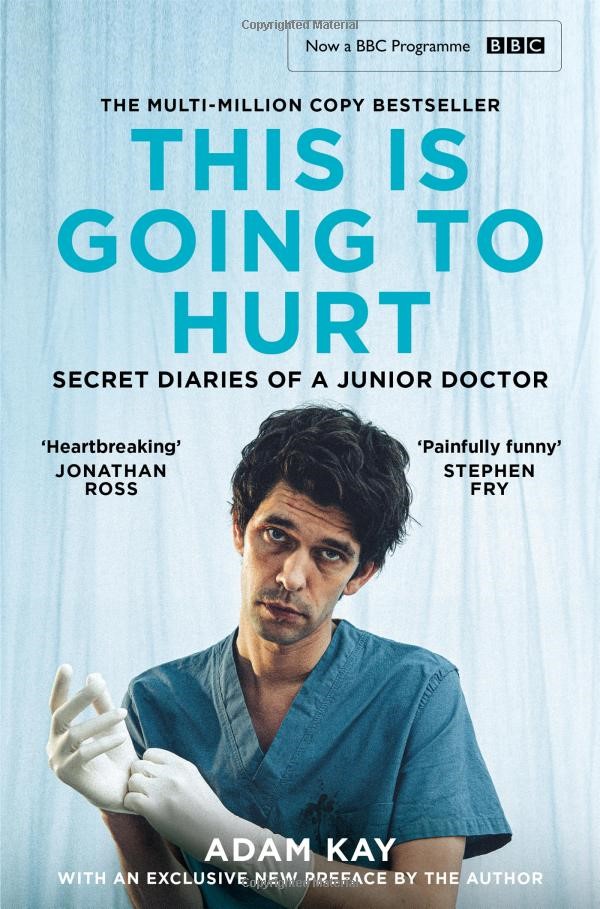

[In case you’re wondering, I was reading This Is Going to Hurt by Adam Kay. The book is nonfiction. Kay tells stories from his years as a doctor, before he quit to pursue a career as a comedian and a writer for TV and movies. Doctors from all over the world have written to tell him that his experiences as a doctor mirror their experiences as doctors. If you’re a doctor, you’ll probably like the book because you’ll appreciate that someone gets you and understands what the job is like. If you’re not a doctor, you should read the book because you’ll gain insight into a profession that we might all assume we understand because we go to doctors, but we really don’t.]