Ever have someone tell you to keep your head down? I interpret that to mean I should put my head in a book. And sometimes a book is the best place to be. I’ve been hanging out in a lot of books lately.

The Ski Jumpers by Peter Geye. I read The Ski Jumpers because I read The Lighthouse Road and Safe from the Sea, both beautifully written novels. Geye writes stories with brooding, flawed characters who are self-reliant and tough, yet vulnerable, which makes me like them and root for them. The vivid landscapes in Geye’s novels become a character that his protagonists must work with and sometimes fight against. In The Ski Jumpers family secrets gather like dust bunnies hiding in the dark, under a heavy, nearly immovable antiquated piece of furniture. Because each family member knows only a part of their family’s secrets, misconceptions develop and resentments grow. Pops Bargaard loves his wife, Bett, but she struggles with her own demons, one of which is her inability to love both of her sons. She dotes on Anton while despising Johannes “Jon.” Pops, an accomplished ski jumper in his youth, introduces his sons to the sport. Ski jumping becomes an escape for Pops and his sons. And as the years go by, ski jumping becomes what Pops and his sons talk about when they are still hiding secrets, when they aren’t ready to talk about their pain, when they are holding on to happier times. One of the joys in Geye’s novel is his detailed, vivid descriptions of ski jumping, which fly off the page, taking me along, letting me ski jump with Johannes and Anton. At some point while reading Geye’s book, I skipped to the “Acknowledgments,” and as I had come to believe, I found that he grew up ski jumping, which explained how he could write so intimately about it.

Still Waters by Matt Goldman. I read Still Waters because I’ve read three of Goldman’s Nils Shapiro detective novels: Gone to Dust, Broken Ice, and The Shallows, and enjoyed them all. Still Waters is one of Goldman’s stand-alone novels. It’s a murder mystery, but one that is solved with the help of ordinary people. Siblings Liv and Gabe, who are estranged, must reunite for their older brother Mack’s funeral in their rural northern Minnesota hometown. Mack’s death has been ruled a medical event, but Liv and Gabe receive emails from their dead brother saying he was murdered. While Liv and Gabe try to make sense of Mack’s email and uncover the truth about his death, someone else dies, and it’s clearly murder. Liv and Gabe discover mysterious letters in a box that belonged to their deceased mother, and they suspect the letters hold the key to Mack’s death and the second murder. This smartly woven mystery with multiple theories and a number of potential suspects kept me guessing. Plus, I could read it before I went to bed and still drift off to sleep without checking under the bed. (I like mysteries without psychopathic serial killers.) Goldman’s mystery does have some scary moments, but only enough to make the heart race a little.

Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing. I read Endurance by Lansing because I like reading about shipwrecks. (Click here for proof.) The Endurance isn’t wrecked on a shoal or reef, she isn’t tossed over by a violent storm, and she isn’t irreparably wounded in battle. Instead, she has purposefully sailed into the Weddell Sea filled with ice floes, looking for a place to land on Antarctica. She is stalled by the ice, which sandwiches her in a death grip, squeezing and squeezing until she groans, and parts of her snap like toothpicks. After becoming unseaworthy, her crew have no choice but to abandon her and their mission to be the first to cross the width of Antarctica using sled dogs. Now the twenty-eight men must survive the beyond-bitter cold, the howling winds, and the snow and rain while hoping to rescue themselves. When Alfred Lansing wrote this book, he had access to the daily journals kept by some of the men, and he was able to interview some of the survivors. Lansing took great care to write an accurate and descriptive account of one of the greatest survival stories, and his book is a tribute to the human ability to put one foot in front of the other and to cling to hope. When Endurance was published in 1959, it was a critical success, but not a commercial one. By the time the book became a commercial success in 1986, Lansing was dead. If you read this book curl up with a blanket and a cup of something hot! This book chilled me to the bone!

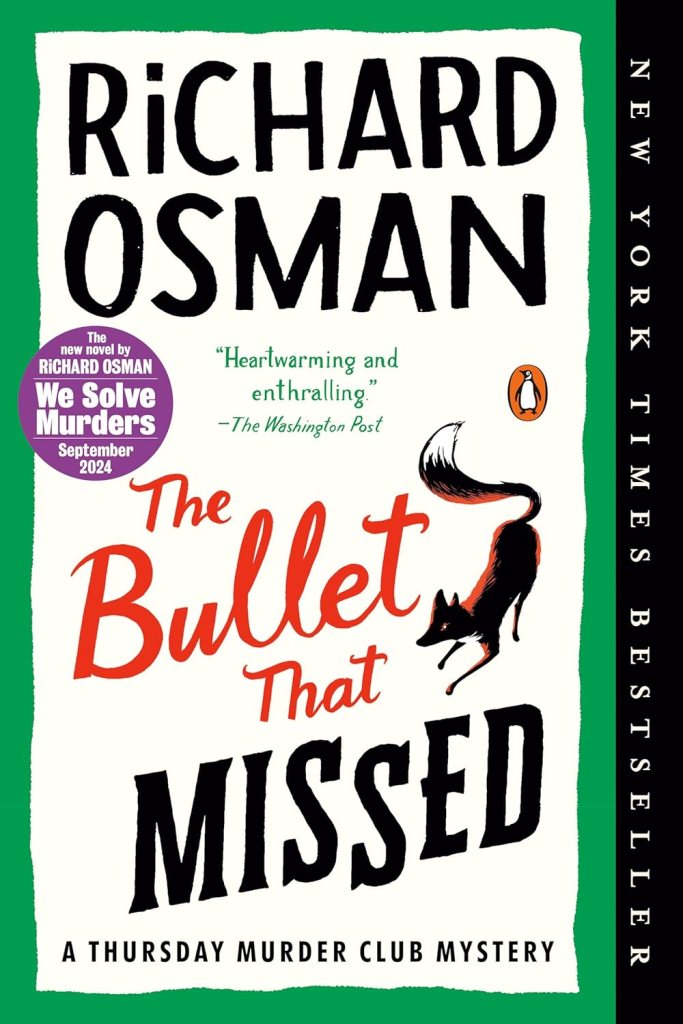

The Bullet that Missed: A Thursday Murder Club Mystery by Richard Osman. I read this book because I read the first two books in the Osman’s series, and they were fun, fun, fun. These murder mysteries are a treat. They are cozy but do have some un-cozy scenes. (And yay! No serial killers, which are so overdone.) Most of the main characters live in a retirement home in the English countryside. While they participate in some of the traditional retirement activities, they have one that’s unusual — they meet on Thursdays to look at cold cases that haven’t been solved. The unsolved murders somehow become entangled in a new murder case, which then also involves the police. One of the characters, Elizabeth, is a former MI-6 agent, and as it turns out, it’s not easy for her to give up the thrills of spying and sleuthing. Her fellow retirees join in the criminal-case-cracking adventures. This mystery series earns top kudos from me for its characters, its dialogue, and its plots. Most of the characters are senior citizens, but that doesn’t mean they have checked out of life. The older characters in the book are presented as people, who all have the same hopes, dreams, desires, and brains as the younger characters, even if the older ones do occasionally battle aches and pains. Osman’s snappy dialogue creates characters that are witty and quick thinking, conversations often drip with verbal irony and humorous understatements. The criminal characters are well-developed, too. They are brilliant and devious, but, of course, never a match for the Thursday Murder Club. While you could read these books out of sequence, I suggest they are best read in order.

Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. I read this book because I walked into Apostle Islands Booksellers and saw it prominently displayed on a shelf. I’ve had people say to me, “Have you read Slaughterhouse-Five? No? Well, you should!” I’ve read articles where writers suggest to their readers, “If you haven’t read Slaughterhouse-Five, you should!” And there it was — Vonnegut’s book — on a shelf, looking at me, waiting for me, so I bought it. Slaughterhouse-Five is described as an antiwar book focused on the firebombing of Dresden in 1945. It follows Billy Pilgrim, a WWII veteran, who time travels from his old age to Dresden, to his wedding day, to life with his family, to a veteran’s hospital, to a planet in outer space, to his youth, like a pinball pinging across a fantasy-themed pinball game. I’m not listing Billy Pilgrim’s time travels in the necessarily correct order; besides, as the story unfolds, Billy travels back and forth among these places in time. But Vonnegut clearly had a plan, and as I read the book, it not only made sense to me, it all worked seamlessly. I never felt like I was being yanked around. A book like Slaughterhouse-Five is hard to explain in words. I like it for its satire, its experimentation, its ambiguity and clarity, and its themes. I like Vonnegut’s simple, but powerful sentences. Slaughterhouse-Five is often spoken of as anti-war novel, and that theme runs through it. However, Vonnegut’s slim novel is thematically rich, and there is much more being said than war is terrible. As I read the novel, I sometimes thought about “The Swimmer” by John Cheever. Raymond Carver’s short stories also came to mind.

Time to go keep my head down in a book. The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride is waiting for me.