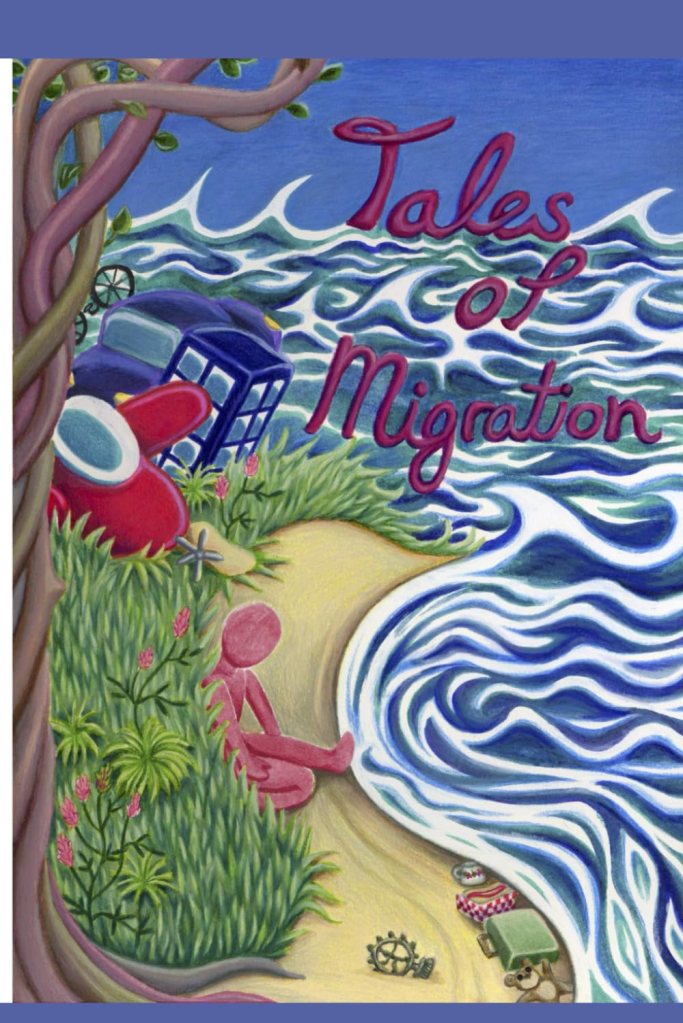

My essay “A Journey with Monarchs” was recently published in Tales of Migration by Duluth Publishing Project. Professor David Beard (University of Minnesota-Duluth) and a group of his students spearheaded this project, from the call for submissions to the finished project. This is the second time I’ve had an essay selected for one of their anthology projects. I appreciate the hard work and dedication of Beard and his students, who all strive to make the experience memorable for their writers. In the spring after the selections are made, they always host a reading, and invite the writers to read their pieces. It’s a wonderful time. I enjoy meeting the other contributing writers, and listening to them read their work.

My essay was inspired by a monarch I saw in Petoskey, Michigan, on a chilly October day. The monarch clutched a pink cosmos flower, and it didn’t move when I approached it. Its behavior so intrigued me that I began to research monarchs and their migration habits. My essay is a creative nonfiction piece of nature writing. For the nonfiction part, I carefully researched all of the information by reading books and online articles from reliable sources. For the creative part, I used some literary devices that I hoped would make the essay enjoyable for people to read while learning about the wondrous migration of monarchs.

[The Tales of Migration anthology is available on Amazon. For more information, click here.]

I’ll never forget the reading for Tales of Migration because I got lost . . .

After this year’s reading, I struck up a conversation with one of the poets whose work appears in Tales of Migration. I had met her the year before when we both read our pieces from Tales of Travel. We left the meeting together and kept visiting. We had parked in different lots, but I kept walking with her because I enjoyed her company and conversation. I figured I would just walk around the outside of the buildings and return to my car. After all, it was a nice sunny evening, the UMD campus wasn’t that big, and I hadn’t gone that far out of my way.

Ha! It didn’t work out as I planned. After I exited the building with the poet, she walked off to her parking lot. I turned the opposite direction and walked off to my car. But I couldn’t find the lot in which I had parked. I walked around buildings. I set the GPS on my phone to walk mode, but it was no help. It was around 7:00 on a weeknight and the campus was devoid of students.

I walked in circles for almost twenty minutes. If it had been dark, I would have been panicked. But the skies were a bright, beautiful blue and considering what spring can be in Duluth, it was fairly warm. I have such a poor sense of direction to begin with, and faced with a random placement of large buildings connected by a maze of passageways, I began to feel stupid and frustrated. I felt trapped inside a bad episode of The Twilight Zone.

I decided I needed to reenter the doors I had exited from with the poet. I retraced my steps back through the liberal arts building and to the room where I had done my reading. From there I felt I could find the engineering building that I had walked through on my way to the liberal arts building before my reading.

But it wasn’t that easy. I had gotten so turned around and addled that I had a hard time remembering how I had originally come through the buildings, which were connected by long and meandering hallways. And to complicate matters, the floor levels in one building don’t always match up to the floor levels in the next building.

I asked a student if he could give me directions to the engineering building. He shook his head and said, “I don’t know. I’m a liberal arts major.”

“I was a liberal arts major, too,” I said, as if that explained why I was lost. He was not the only person to apologize about not being able to direct me to the engineering building. Perhaps liberal arts majors aren’t hardwired to locate engineering departments. On a large campus, many students may never need to visit certain buildings. I went to a small college, and I had classes in every building on campus.

Finally, someone was able to help me. Once I found my way into the engineering building on the correct level, I recognized where I was and located the right exit. My car was where I had left it. Dusk was descending, and I was relieved. It’s not fun being misplaced.

I had known all along where I was, and yet I had been so lost and turned around at the same time. I thought about the irony. I had just read for Tales of Migration, filled with poems and essays about moving from one place to another, sometimes covering thousands of miles. I thought about migrating people all over the world who would know the names of their new homes, yet still be lost and turned around, arriving in a land they had never been before, whose culture they had never experienced. They would have mazes and passageways to navigate, all of which would play out over years, instead of the thirty minutes in which I had been lost.