Last September when I traveled to Shetland, I bought some yarn at Loose Ends and Anderson & Co., both shops in Lerwick.

Shetland is known for its yarn shops, knitted goods, and expert knitters. I was in Shetland September 15 – 20. If I’d gone eight days later, I could’ve taken part in Shetland Wool Week, an annual event, which runs in late September/early October. But having never been to Shetland before, I went to experience its natural beauty, so I spent lots of time outdoors. According to the guide books, the month of September is a quieter part of Shetland’s tourist season. The weather is more unpredictable, and the puffins, a popular attraction, have flown to warmer climates for the winter. But fewer tourists mean less congestion, and that appeals to me.

In late September/early October, Shetland’s weather begins to turn, and it becomes a place of cold temperatures, gale-force winds, sideways rains, and thick gray skies, so sight-seeing tourists shy away. It’s a great time of year to have a knitting conference filled with indoor gatherings. Of course, stormy weather can show up anytime in Shetland, but it becomes more prevalent as September runs into October and winter settles in. Shetland winters are perfect for knitting, as demonstrated by the large quantities of knitted goods to be found in shops, museums, and heritage centers throughout Shetland. After all, I bought four skeins of yarn with the idea that I would knit scarves during northern Wisconsin’s upcoming winter. I also bought three wool sweaters in Scotland because I’m never going to knit a sweater.

I knit beautiful scarves, as long as the pattern is simple and repetitive, and there are no cables involved. Or lacy-like patterns. Or miniature figures or graphic designs prancing across the scarf. Also, no increasing and decreasing stitches. But otherwise, I make nice scarves because I select pretty yarn.

I don’t knit sweaters, slippers, or hats. Only scarves. Although, in the past I have knitted a few dishcloths. But that’s like knitting a miniature square scarf.

Long ago, I tried to knit something more complicated. When I was a senior in high school, I signed up for a community ed class so I could learn how to knit something other than scarves. I selected a pattern for a simple pair of slippers. Because the class was in the fall, I decided I would give the slippers as a Christmas gift to some lucky family member. I went to class and learned how to read a knitting pattern, how to increase and decrease, and how to gauge stitches — in theory. By the end of the class, I had two forest-green slippers — in two different sizes. Since none of my family members have mismatched feet, I couldn’t give the slippers to anyone. Eventually, I threw them away.

I never again tried to knit anything that required I gauge my stitches so the left side of something would match the right side of something. I gave up after one try. I’m like that with some things: I’ll quickly throw in the “mismatched slippers” and call it a day.

I took one year of high school math. I studied hard, but I struggled and I hated it. Thankfully, at that time the state and my high school only required one year of math. As sophomore I took German instead of geometry. I did the same with downhill skiing. I tried it once. I fell every time I went down the slope, and I nearly broke my arm while using the tow rope. I never went downhill skiing again. My attempts at cake decorating, shorthand, sewing clothes, woodworking, and agility training with my dog Ziva met the same fate.

But I can be tenacious. My younger sister learned how to ride a bicycle before I did. I couldn’t get the feel for balancing my body on the bike. But I wanted freedom from training wheels, so I spent hours practicing in our driveway. The first time I went roller skating, I fell again and again. But during the moments I managed to remain upright, I loved it. So, I kept going. The same for cross-country skiing. I kept falling and getting up, wondering if I’d ever maintain my balance on the skinny skis, but I loved it. So, I kept getting up. For years bicycling, roller skating, and cross-country skiing were some of my favorite pastimes.

I took three years of Spanish in high school. Although I sometimes struggled with pronunciation and didn’t grasp the verb tenses, I took Spanish in college because I loved learning a language. I still remember the day, when the Spanish verb-tense thing clicked for me. Professor Stevenson stood in front of an antiquated blackboard in Old Main delivering a lesson about verb tenses. He wore a pair of dress trousers, a white shirt, and a bow tie. I sat in a modern desk, taking notes. I wore a pair of faded, patched blue jeans and a pale-yellow T-shirt with the rainbow-colored word Adidas printed on the front. I’m sure my face lit up like a light bulb. At the same time, I realized that was how verb tenses worked in English. I was giddy with Spanish and English grammar knowledge for the rest of the day. I enrolled in Spanish II the following year.

So, what makes the difference between something I’m willing to keep working at and something I give up on? It depends on the amount of joy I experience in between my feelings of frustration and inadequacy. If there is something I love about the new activity I’m learning, I keep going, even if I look foolish while others are quickly grasping the skills. I don’t care about becoming an expert. I just enjoy my level of competence. I never learned to roller skate backwards or do spins. I never became a fast cross-country skier. I’m not fluent in Spanish. I’ve never again attempted to knit anything other than a scarf, but I love knitting them. I’ve made them for my grandmothers, mother and mother-in-law, sisters, nephews, nieces, grandkids, and friends. I love the meditative, mindless, repetitive movements of combining purl and knit stitches as I watch the colors and patterns meld together.

I’ve never regretted giving up on high school math classes or advanced knitting or downhill skiing or any of the other endeavors I tried briefly then ditched. But we’re taught to try and try again. If at first you don’t succeed, try again. The only failure is giving up. Give 110%. If you’re not failing, you’re not trying. Fall down eight times, get up nine.

But sometimes failure teaches us when it’s time to cut bait and walk away. To stop banging our head against the wall. To stop throwing good money after bad. To stop turning the other check, only to have that one slapped too.

Failure is normal, and sometimes we have to keep at it, and in the end, we’re glad we persevered. But failure can be a way of telling us that maybe we aren’t suited to something. That sometimes it’s okay to give up, and knit scarves.

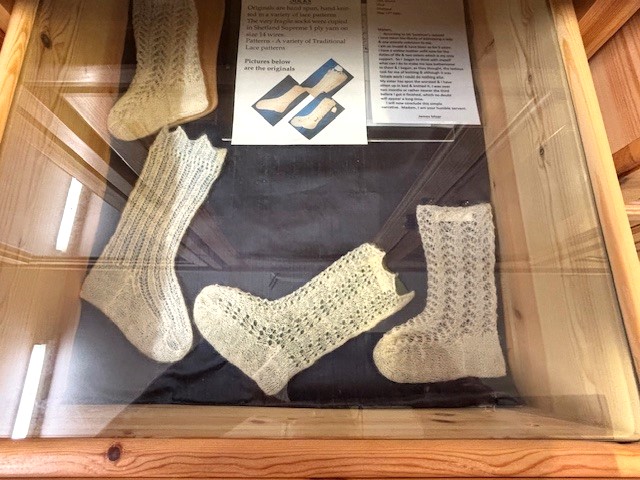

[The pieces below are knitted with a very fine wool. They take a crazy amount of hours to complete. The delicate scarves, shawls, and baby garments are used for life’s special occasions, such as weddings and baptisms. Whether made by a family member or purchased in a shop, these pieces are treasured and passed down through generations. I saw some exquisite lacy shawls and baptism gowns for sale in local shops in Shetland. They cost two to three times more than wool Shetland sweaters, reflecting the time and skill needed to produce them. And I’d bet the artisans are still woefully underpaid.]