Today Persimmon Tree published my flash essay “I Wish I Could Take You with Me” as part of their Short Takes section with the theme Verbal Lightening.

To read my essay click Short Takes, Verbal Lightening, and scroll down toward the bottom.

Today Persimmon Tree published my flash essay “I Wish I Could Take You with Me” as part of their Short Takes section with the theme Verbal Lightening.

To read my essay click Short Takes, Verbal Lightening, and scroll down toward the bottom.

I loved her voice and the way she danced and strutted across the stage, giving every song her all. She was power and elegance and talent.

As kids my sisters and I loved Ike and Tina Turner’s version of “Rolling on a River.” We loved how they started the song out “nice and easy” because as Tina said, “we never, ever do nothing nice and easy” then halfway through they rocked the song like a river bursting over its banks.

We called Milwaukee’s Fun-Loving WOKY at 920 on your AM dial. They took requests. So we asked, “Can you play ‘Rolling on a River’ the way Ike and Tina Turner sing it?”

“Sure,” someone at WOKY said. After all, they were Fun-Loving.

Instead they played “Rolling on a River” by Creedence Clearwater Revival. Disappointed, we called again and again, asking for the “nice and easy” version. But we were kids, and we pissed them off with our insistence they get our request right. They told us they wouldn’t play Ike and Tina Turner’s version because they’d just played the CCR version.

We gave it a rest. But we called every couple of days, asking to hear “Rolling on a River” by Ike and Tina Turner. Fun-Loving WOKY at 920 on your AM dial never honored our request. After a couple of weeks we gave up.

Today I didn’t need to call a request line to hear Tina Turner sing “Rolling on River.” I’ve got YouTube. I watched three different versions of Tina sing and dance to the best version ever of “Rolling on River.” And I was twelve years old again.

Ike and Tina Turner live in 1971 singing “Proud Mary.”

Tina Turner live in the Netherlands in 1996 singing “Proud Mary.”

Tina Turner live in 1999 singing “Proud Mary” with Elton John on piano and a duet with Cher.

I look out my kitchen window. I can see Mrs. H’s house. She died last November at the age of ninety-one. Yellow caution tape runs from the road, past the side of her house, and toward the back of her yard where her magnificent gardens, filled with daffodils and tulips and other flowers I can’t name, bloom every spring. The caution tape evokes the feeling of a crime scene, but it’s simply there to keep the people at the estate sale from trampling through the gardens. Cars park up and down her block and the next block and on my block. People line up outside her front door, waiting to enter her home, hoping for bargains at the estate sale. I think about Scrooge’s visit with the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come and the scene with gleeful characters scavenging through the belongings of the recently dead Scrooge.

I’m not saying Mrs. H was like Scrooge, she wasn’t, or the people in line are gleeful, they’re not, but this is what I think about. I waver about whether or not I will go to the estate sale. Going into Mrs. H’s home — looking at her possessions, which under normal circumstances would have been in cupboards and closets and drawers — feels like an invasion of her privacy.

I’ve lived in this neighborhood for twenty-seven years. Mrs. H was here when I moved in, but I’ve never been inside her house. We were of different generations. But I liked her well enough and enjoyed our brief chats when she walked by my house, first with one Miniature Schnauzer then later on after that dog died, with another one.

Even though going to the estate sale feels like an invasion of her privacy, I’m curious about what her house looks like inside. It’s adorable from the outside — one of my favorites on the street. I might buy something as a keepsake.

I keep watch out my kitchen window, and when the line of people is gone, I grab my purse and walk to Mrs. H’s house. I don’t have to knock to enter, but I do have to take off my shoes.

The front door empties into the living room filled with used furniture. There is a three-person couch for $800, a small outdated stuffed chair and ottoman for $700, and a four-person couch for $900. So much for bargains.

I notice the picture hanging on Mrs. H’s wall has been straightened and marked with a $40 price tag. It’s from the 1980s, like something that hung in a middle-class hotel. For almost a year before Mrs. H died, the picture hung crooked on her wall. Every evening when I walked my dogs past her house, I wondered why she didn’t straighten it. Eventually, I came to believe the crooked picture meant something was wrong with her.

One afternoon, as I walked my dogs by Mrs. H’s house, I ran into her daughter. I asked how her mother was doing. She answered, “Not good.” Her mother was suffering from dementia. I told the daughter about the crooked picture on the wall, that it had convinced me something wasn’t right with her mother. After our conversation, I thought the daughter might straighten it, but she didn’t. The picture remained crooked for months, a signal flag of Mrs. H’s difficulties.

I wander through the house. Its rooms are small, but neat. Simply decorated but bland. Everything is clean. There isn’t much for sale in the house. I get the impression that Mrs. H didn’t like to clutter up her small home with lots of stuff. Objects are $10, $15, $20, $30, $50, $60, $90, and more. If this were a rummage sale, the same objects would be a fraction of the cost. I don’t buy anything, and I don’t stay long. I feel like an interloper. But once outside, I take pictures of some beautiful flowers in one of Mrs. H’s gardens.

Everything changes. Mrs. H is gone. Mr. H died eight years ago. The dishes and tools and clothes and knickknacks that made up their lives are being sold. Mrs. H’s gardens didn’t winter well, and the daffodils and tulips, usually plentiful and jovial, are sparse and lonely. Someone new will live in the house. Mrs. H’s daughter-in-law isn’t sure if the family will sell the home. Perhaps one of the family will live in the home. If they sell it, I hope someone with children will move into the house. When I first moved to this neighborhood, it was filled with children, including my own, and I miss the shouts and the laughter of children playing outside.

[This personal essay was published in the April/May 2023 issue of Our Wisconsin. Last year and this year, the editors asked for submissions on the theme “Lessons Learned from Mom” in honor of Mother’s Day. Our Wisconsin is a print-only magazine. Happy Mother’s Day to everyone who mothers someone.]

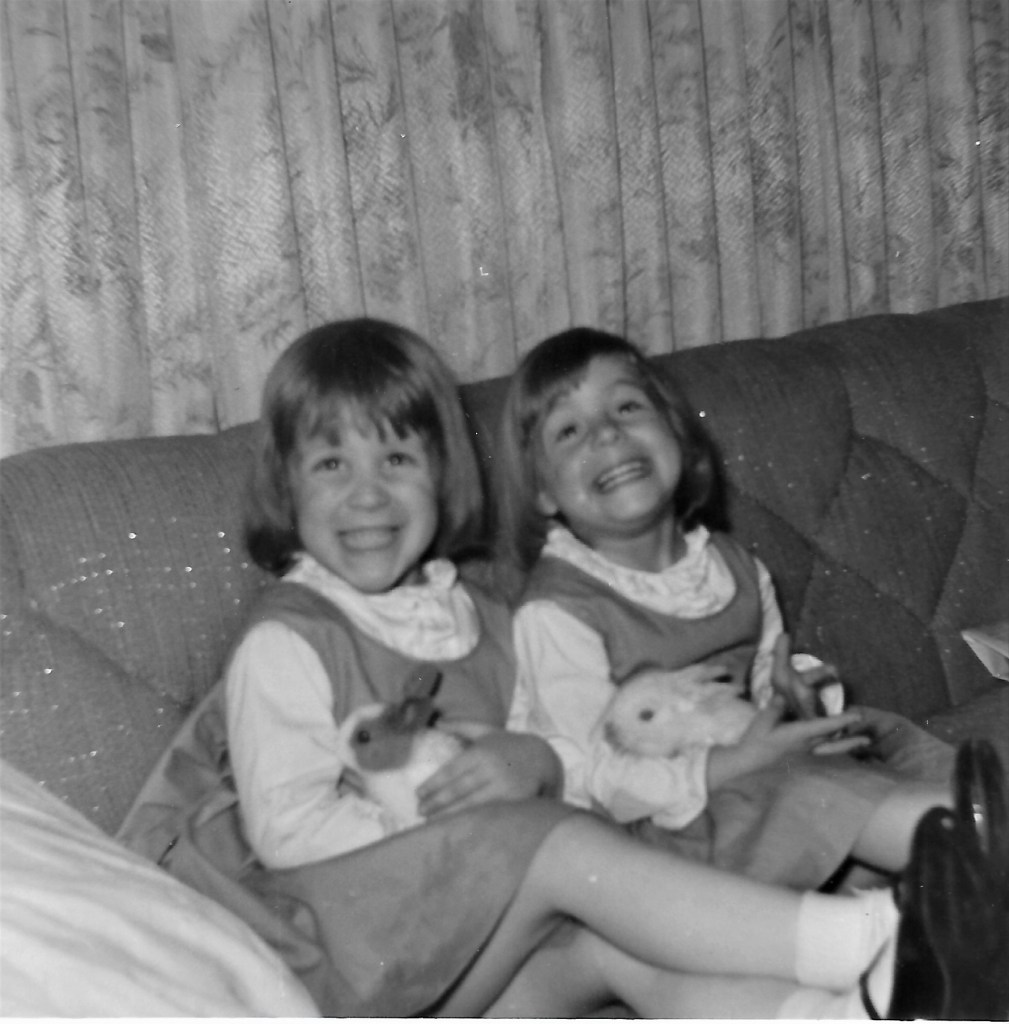

Mom taught us to think about how our actions affected other people. My sister and I were about 5 and 6 the first time I remember Mom delivering this lesson.

We lived in rural Franklin, Wisconsin, a mile north of the Racine County border. Sometimes Mom shopped at a small, independent grocery store. It was nearby, and she liked the store’s butcher shop.

On an autumn day around 1965, Mom loaded us into the car for a trip to the local store, which my sister and I relished. The vibrant-colored penny candy located by the checkout counter made our mouths water. Our pockets normally jingled with coins from our piggy banks, but Halloween was creeping up, so Mom had nixed buying sweets. “You’ll soon have plenty of candy,” she said. “Leave your money home.” We grumbled but left the house with empty pockets.

The store was old-fashioned compared to the supermarket where Mom usually shopped. At the supermarket, we had to stay with Mom, so we didn’t get lost. At the local store, we could roam. Mom could either see or hear us from anywhere in the store.

Mom walked to the back of the store to talk to the butcher. My sister and I remained near the candy. We yearned for Life Savers.

While Mom talked to the butcher, our chance arrived. The cashier left the counter while other shoppers browsed the aisles. I grabbed a roll of Life Savers and stuffed it into my pocket. “We’ll share them,” I whispered to my sister.

Mom finished shopping and paid the cashier. The pilfered goods rested in my pocket. My sister and I didn’t attempt to eat them in the backseat on the way home. Mom had something akin to eyes in the back of her head.

After returning home, Mom put groceries away in the kitchen, and my sister and I sat in the family room, opening the Life Savers. A debate about favorite flavors, eclipsed caution. Mom heard us arguing and appeared in the doorway connecting the kitchen to the family room.

“Where did you get those?” Her voice squashed our argument and dread rendered us speechless. We knew that she knew.

“Did you pay for those?” she asked.

We shook our heads. Lying to Mom wouldn’t work. She’d call the store to check.

“Get a nickel from your bank.” She glared at us. “You’re returning the candy, paying for it, and apologizing to the owner.”

The words, apologize to the owner, were the harshest part of the punishment. The butcher, a muscular man, owned the store. He wore a white apron splattered with blood. He chopped meat into chunks with sharp knives. Would he be holding a big knife when my sister and I had to stand before him and admit we robbed him? Would he yell at us?

Driving back to the store, Mom painted various scenarios, hoping we’d absorb what she said. She wanted us to understand the far-reaching effects our seemingly insignificant 5-cent theft might cause.

“You didn’t just steal from a store—you stole from the owner, a person.”

I hadn’t thought about that.

“He has a wife and children. If people steal from him, he can’t pay his bills. His family will go hungry.”

I pictured his starving children.

“He won’t be able to pay his employees, and their families will go hungry.”

I pictured more starving children. Guilt joined my apprehension.

“You stole from him, his family, his employees.”

I pictured a line of angry people.

“If he doesn’t make money, his store will close. His customers will be unhappy.”

Mom’s talk continued all the way to the store. I don’t remember what the butcher said to us, but he wasn’t holding a knife and he didn’t yell.

I never shoplifted again. When my 7th grade friends wanted to steal gum from a drugstore, I refused to go with them. I remembered Mom’s lesson—I wouldn’t just be stealing a pack of gum.

Mom applied this lesson to other situations, compelling us to be mindful of people’s feelings, explaining thoughtless behavior hurts people. But the hidden gem in her moral? We learned humanity.

[Essay appears here as it was submitted.]

Today my dear friend Sandi would’ve been eighty years old. She isn’t here to celebrate because she died almost five years ago. But if she were here, she would tell everyone she didn’t like having birthdays, she didn’t want to celebrate her birthday, and if anyone mentioned her birthday, she would be angry. One year her family took her at her word, and she was deeply hurt. (I hadn’t been so foolish.) I knew her birthday needed quiet acknowledgement: a card in the mail, a text, an invitation to lunch for “a chance to chat,” and a small inexpensive, but just-what-she-wanted gift.

The first time I met Sandi was in a law office. She was a paralegal, and I was a newly hired paralegal. When our mutual boss introduced us, he added, “Vickie has an English degree.” (I rarely tell people I’m an English major because I’ve learned they think I’m secretly judging their grammar. I also don’t want them secretly judging my grammar.) Sandi remarked, “Oh, good. That’ll be useful because I can never keep the possessive-apostrophe-s rules straight.” I told her I struggled with affect/effect and to lie vs. to lay. I thought about Humphrey Bogart and Claude Rains in Casablanca. I suspected the sharing of our grammatical weaknesses was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Later we would laugh about this. She had been intimidated by my being an English major. But it turned out, having attended a private, rigorous Baptist school, she had some good grammar chops herself.

I was forty-five when I met Sandi, who was sixteen years older than me. And the first time I met her oldest son, he said, “I’m surprised that given the age difference you and my mom are such good friends.” I answered, “Your mom’s a little young for me, but I try to be tolerant.” He burst out laughing with the same raucous from-the-bottom-of-his-belly laugh that often erupted from Sandi. “Point taken,” he said. He knew exactly what I meant about his mother.

One year, just after Sandi had become sick, I cleaned her garage for her as a birthday present. Her son owned the house where she lived and he was coming to visit. Through no fault of her own, the garage was a mess and she knew he would be upset. She couldn’t get the responsible party to clean it, and she didn’t have the strength to clean it herself. However, she was embarrassed about me cleaning up the mess, until I pointed out to her that it was a free birthday present, and weren’t we always about free or very inexpensive presents? It took me hours over the course of a couple of days to sort, stack, and sweep the mess into submission. But Sandi and I had some good times going to the Goodwill and to the hazardous waste disposal site together. If you can have fun going to the dump with someone, that’s friendship. A week later when her son arrived, the garage was shipshape, and he complimented his mother on how good it looked. She told him it looked good because she had been given the best birthday present ever.

I think of Sandi every day, and on some days, I cry because she isn’t here. But I did my heavy sobbing when she was still alive. I’d come home from visiting her and sit on my wooden deck stairs and sob.

A picture of two white ducks paddling on water that her niece painted hangs on my family room wall. Because she knew I loved the painting, she gave it to me before she died. A quilt graced with cheerful red cardinals perched in pine trees that she made for me rests on my bed. And when I turn out the lights before going to bed, two LED nightlights glow from outlets in my house, ready to light my way should I need to move about in the dark. When she gave the motion sensor nightlights to me, I looked at her rather dubiously. I’m not a gadget person, but she was. She had a light-up-in-the-dark toilet seat that could be set to glow in different colors. She assured me I would grow to appreciate their usefulness. But what I’ve really come to appreciate is that I think of those nightlights as her watching out for me.

Sandi and I agreed on important stuff. Like Stephanie Plum novels by Janet Evanovich were the funniest, but the casting for the movie One for the Money was awful. That Antiques Road Show was binge-worthy, but we should always begin watching it with Dairy Queen treats in hand. That potato salad should always be made from scratch and only with real mayo. That sometimes husbands and children had to be humored.

We loved British sitcoms, The Full Monty, and inside jokes. We shared an irreverent, nonlinear, cheeky sense of humor. We could poke fun of each other, ourselves, and situations, making one another laugh out loud, sometimes hysterically, which always made her snort.

But we always knew when to batten down the hatches and look out for one another. That is, after all, why she gave me the motion sensor nightlights.

Mrs. Luepke is part of my childhood, but I don’t remember her. She was my parents’ neighbor when I was born. But she is a legend in my mind because she taught my mother how to make a wunderbar German potato salad.

I grew up hearing stories about Mrs. Luepke who kindly shared cooking tips with my mother, who in 1958 was a young bride with no cooking skills.

My mother made Mrs. Luepke’s German potato salad for special events, holidays, and picnics. When I was old enough, I helped. The kitchen filled with the smells of boiling red potatoes and sizzling bacon. Followed by the sweet, tangy smell of vinegar and sugar simmering on the stove in a bath of bacon fat and butter roux, which would be poured over the potatoes, bacon, and sliced green onions.

My favorite way to eat the German potato salad was when it was warm. I’d sneak a spoonful (or two) while I mixed the ingredients together.

For years the recipe had been lost. But this winter my mother discovered that her brother, who now lives a thousand miles away, had a copy of the recipe. My mother copied down the ingredients on a piece of small paper, and handed it to me when I visited her for Christmas last year. The paper contained no instructions, so when I made the potato salad, my mother explained the steps. Our mother-daughter-German-potato-salad project was the highlight of my Christmas. And the salad tasted as wonderful as I remembered it tasting when I was a child.

If you make the potato salad, think of Mrs. Luepke. During the years when her recipe was lost to my mother and me, I never found another German potato recipe that tasted as good as hers. In some small way, I’m glad to keep her memory alive.

The Ingredients

The Recipe

In 1924, Seegar Swanson and Elliott Nystrom, both twenty years old and friends since elementary school, decided to take a year off and tour the perimeter of the United States, making sure to visit the four corners of the country: Maine, Florida, California, and Washington. They saved money for their trip and bought a 1919 Model T Ford touring car for $125. They left Ashland, Wisconsin, in the late summer of 1924, and returned to their hometown in 1925. The trip took about a year because they worked at different jobs along the way. Also, Swanson points out, more than once, that the top speed of their Model T was 25 mph, if the roads were good.

Along the way Swanson and Nystrom kept a log of their experiences and expenses and took many photographs. Additionally, they wrote long letters home. After Swanson and Nystrom finished their journey, Swanson attended Northland College in Ashland. In 1936, he became the editor of the Superior Evening Telegram and later on he worked at the Duluth News-Tribune. After a long career in journalism, he retired at seventy-two. At the age of ninety, when he started writing Ford Tramps, he had his detailed resources and years of writing experience. He spent three years writing his book, and his hard work and dedication paid off because Ford Tramps is a well-told story that captures the mood of the country and its people in the mid-1920s and gives readers a glimpse into the daily lives of ordinary Americans and the places they lived.

Published in 1999, Ford Tramps is out of print, so if you want to buy a copy from Amazon, it will be used and it will cost between $56.26 and $154.63. Thriftbooks has one copy listed for $59.99. I paid under $20 per book when I bought two copies in 2000. I gave one to my father, and I kept the other.

My father read Ford Tramps right away and loved it. I cracked open my copy in March 2023. It’s amazing how fast twenty-three years can drive by. And if I hadn’t read a blog about autocamping in the 1920s written by Chris Marcotte, my copy of Ford Tramps would still be parked on my bookshelf.

I wish I’d read Ford Tramp years ago, when my father was still alive so we could’ve talked about the book and why we liked it. Even though we never had that conversation, I’m going to tell you why I think he enjoyed the book so much.

He liked it because Swanson’s descriptions of the 1919 Model T bring the car to life. The Model T that Swanson and Nystrom drove had three pedals on the floor and a lever by the door side of the driver’s seat that controlled the transmission, and it had a lever on the steering wheel that controlled the throttle. A complex coordination between feet and hands was needed to shift gears. Machines fascinated my father. He loved being a part of them, manipulating them, controlling them, understanding them, and pushing them to their limits. He drove cars and motorcycles, and he flew planes. Just as Swanson and Nystrom had to learn the personality of their Model T and what it could and couldn’t be asked to do, my father took pride in mastering his cars, motorcycles, and planes.

He liked the book because the Model T broke down on the road, and its tires often went flat. Swanson and Nystrom played nursemaid to the Model T, learning what they could fix themselves or rig up until they could afford a mechanic. My father, a savvy mechanic, would’ve reveled in the Model T’s challenges. Sure, when the car broke down, he would’ve sputtered and cursed. Then he would’ve put the Model T in its place and back on the road. He owned his own garage where I once heard a customer with an old sports car ask him, “What if you can’t get a part?” My father answered, “I’ll rig something up, and it’ll work.” That 1919 Model T would’ve been putty in my father’s hands.

He liked the book because he was in his 60s when he read it, but he could be young again, on a vicarious adventure from the comfort of his couch where his standard poodle and his greyhound curled up near him. In 1955, he was eighteen when he moved from a small unincorporated town in northern Wisconsin to the big city of Milwaukee, hoping to make his way in the world. My father never took a road trip like Swanson and Nystrom, but in a small way, he liked to travel and experience new places and meet new people. Swanson and Nystrom met many interesting and kind people while working odd jobs and autocamping. Swanson’s writing breathes life into these men and women, allowing readers to work beside them in an orchard picking crops or sit with them around a cookstove as they share stories and food with other autocampers.

My father liked the book because Swanson included many photographs, maps, log entries, expense accounts, and receipts. It was fun to see what food, lodging, camp fees, car repairs, and other necessities cost in the mid-1920s. Swanson and Nystrom also reported how much they were paid doing manual labor. My father, an avid photographer, took photos when he traveled. After he had his film developed, he would show you ten pictures of the same vista, then ten pictures of the same museum display, then ten pictures of the same man who took him out fishing on a charter boat. My father considered maps to be among the most useful items in his life. He used them when driving to someplace unfamiliar, and he used them to plan his flights from one airport to the next. As a pilot he kept a log of all his flights, and as a businessman he kept expense accounts and receipts.

My father liked the book because the Ford Tramps spent time in his beloved state of Arizona. He moved to Arizona when he was forty, and he thought his adopted state was amazing. Swanson and Nystrom marveled at the Petrified Forest, amazed that trees had turned to stone. The pair debated between seeing a bullfight in Mexico or seeing the Grand Canyon, with both of them favoring the bullfight. The Grand Canyon won out because in Mexico, bullfights were only held as part of major holiday celebrations, and it was too long a wait for the next holiday. Some things are meant to be. Swanson and Nystrom fell in love with the Grand Canyon, agreeing it was, as Nystrom remarked, “The greatest thing we’ve seen so far.” They stayed for five days. They hiked to the bottom of the canyon and swam in the Colorado River. They hiked along the rim in both directions, and they attended a Native American ceremony. One afternoon they took shelter in their Model T during one of the desert’s quick moving and furious storms accompanied by lightning that seemed to touch the ground and thunder that redoubled its intensity as it echoed off the canyon walls. My father never tired of watching desert storms roll through Tucson.

I’m at the point in the book, when Swanson and Nystrom have just crossed into California. Even in 1925, in an effort to contain harmful pests, California border patrol officials stopped cars to make sure people weren’t carrying fruit into the state. The Model T was searched from top to bottom because Swanson and Nystrom admitted to having a handful of oranges that they’d been given in Florida. Embarrassed, but having nothing else to hide, they were allowed to enter California. I have eighty-eight pages left to read, and Swanson and Nystrom are about to visit Yosemite Park. I’m sorry my journey with them will soon come to an end.

Someone suggested I sell my copy of Ford Tramps, pointing out my investment in the book had at least tripled. I’m not selling my copy, but if I did I could list it as “like new” because it’s only been read almost once, and I haven’t spilled any coffee on it. I wish I had my father’s copy of the book, but I wouldn’t sell his copy either. However, I would’ve been willing to share one of the copies with someone else. My father would’ve liked that, too.

I think of these mornings as Ansel Adams mornings, when overnight the snow has fallen wet and heavy, clinging to branches, railings, and the sides of houses. The sky is tinted with the blue-gray of first light, and sunrise is moments away. It’s a world captured in gray and black and white.

Aiming my phone out the window, I take color photos, but they come through as black and white. Later when I apply the noir setting to them, the difference between the original and edited photos is nearly nonexistent, so I discard the changes.

Adams, one of my favorite photographers, captured the American West in black-and-white images, and his landscape photos featuring snow are among my favorites. I learned about Adams in a college photography class that I enrolled in because friends were taking the class for their art requirement. Having taken a ceramics class that summer, I didn’t need anymore art classes, but I signed up anyway because the class met on Monday nights when we all went country swing dancing at a local bar. If I was at class with them, it would be easier for us to carpool to the bar. I miss those days of whimsical logic.

That autumn I had a marvelous fling with country swing dancing, but I fell in love with the photography class. My friends spent just enough time completing assignments to earn what we called Charity C’s. But I spent hours photographing people, architecture, nature, and landscapes. And I spent hours and hours in the photo lab developing negatives and printing pictures, experimenting with different papers and exposures. I saved up money and bought my own 35 mm camera, playing with the f-stop, shutter speed, and film speed. I took four more photography classes over the next two years.

I thought about a career in photography, but I was more in love with taking pictures than the idea of earning a living by taking pictures. After I married and had children, my manual 35 found a shelf on a closet and retired. My husband bought me one of those instamatic 35 mm, a point and click camera that used 35 mm film. I used it for years, until I bought a digital camera with an SD card. But now my camera is a smart phone. And I can be a photojournalist wherever I travel or from the inside of my house.

My dog Cabela is fourteen-and-a-half-years old, so in human years she’s ninety-and-a-half. Living with Cabela these days is like living with a very senior citizen. (I’m not sure I like that term. Maybe I’d prefer aged person. But maybe not. It’s February and I get cabin fever in February so I get moody. What sounds good to me one day, sounds awful to me the next day. But this post isn’t going to be about what to call old people. And by the way, winter doesn’t bother me. I don’t care how much snow falls or how many days it has been since the sun has made an appearance. But the quality of the daylight changes in February, and it awakens something in me, and I get cabin fever which recedes sometime in April when I return to ignoring the weather. But this post isn’t going to be about weather either.) It’s about living with an old dog whom I love dearly. And a hardworking grandfather who lost his sight when he was eighty.

Cabela often enters a room and stops abruptly. She stands still, not looking in any direction, and hangs her head, pondering. She’s asking herself, “Why did I come in here?” or “Where was I going?” It takes her a bit to figure it out. I know, I know, sometimes when I go into the basement, I forget why I went down there. But I usually remember as soon as I go back upstairs. And most of the time I don’t forget why I went downstairs.

At night Cabela’s more confused and she often paces. It’s called sundowning, which is not a disease, but a condition that can occur with dementia, and yes, dogs can get dementia. Sometimes I think Cabela has a touch of it. She knows all her people. She hasn’t forgotten when it’s time for her meals, treats, and walks. And she doesn’t mistake the floors for the yard. But she has changed.

On most nights, somewhere between midnight and two in the morning, Cabela begins the restless pacing, the waking up and wandering from the bedroom to the family room to the bathroom. The first time she does it, I get up and let her outside. Lots of older people need to get up during the night and pee, and if Cabela needs to go, she needs to go. It’s not good to hold it. But after she comes back inside, she can’t decide if she wants to sleep on her bed in the bathroom or her bed in the bedroom or on one of the couches in the family room. I hear her paws swoosh on the carpet as she walks by the bedroom on her way into the family room. I hear her walk by the bedroom again on her way to the bathroom where her nails click on the linoleum and her body thuds onto the sheepskin bed tucked between the end of the toilet and the cupboard. I hear her rise up and once again her nails click on the floor, but instead of walking by the bedroom, she enters it. I know she’s looking at me, wondering why I don’t get up. Because I believe she thinks it’s time to get up. Finally, she settles down for a few more hours, but eventually she begins pacing again before my husband and I have to get up.

Last night Cabela was more restless than normal. The only one who slept through it all was Ziva, our other younger dog.

So my grandkids and I took Cabela and Ziva for a walk this morning before it started raining. Cabela can’t walk far, but we went slow. We walked three blocks up, one block west, three blocks down, and one block east. My idea was to give her more daytime activity, hoping she’d sleep better tonight. But we’ve only managed one walk because it’s still raining, and it’s cold, soggy, and windy. It’s not good weather for a “ninety-year-old” dog.

On our morning walk, I thought about my grandpa George who went blind at eighty years old. He didn’t have dementia, but he was restless at night. He kept waking my grandma Olive and asking her if it was time to get up. He’d fuss about who was taking care of his garden or about something that needed attention at his gas station. In the darkness of night, things are always a worry. And for Grandpa, who’d lost his sight, I imagine those worries became terrors.

Before Grandpa George went blind, he still went to work at his station six-and-a-half days a week. He pumped gas and tinkered in the garage. He’d been going to work at his station for over sixty years, rarely taking a vacation or even a day off. He planted a large garden and grew raspberries, strawberries, green onions, sweet onions, new potatoes, russet potatoes, corn, peas, beans, beets, asparagus, carrots, and a few flowers between the rows of fruits and vegetables. He did the sowing and the harvesting, even at eighty years old.

But after he lost his sight, his life screeched to halt, like a pair of rusty brakes on a customer’s old car that he once would’ve fixed. Grandpa George, who got up every morning before six, ate at seven, and opened his station at eight, couldn’t walk from his bed to the bathroom without someone to help him find his way. Grandpa George, who raised the finest garden in town that provided food for his family throughout the summer, fall, winter, and spring, could no longer read the rain gauge or sort his seeds for planting.

Grandpa’s days and nights somersaulted. He dozed on the living room couch during the day when he should’ve been filling someone’s gas tank and checking her oil. He listened to the evening news when he should’ve been checking the corn and pulling potatoes in the garden. At night when he would’ve been sleeping after a day’s work, his mind raced and he kept his wife up with question after question, starting with, “Olive, you awake?”

Grandma Olive tried to keep Grandpa from falling asleep on the couch during the day. At first people came to visit, and he told them what to do at the station in order to close it down, and there were the last crops to reap from the garden, all activities Grandpa oversaw while sitting at the kitchen table, his calloused mechanic’s hands resting on a white oilcloth decorated with nickel-sized cherries.

Someone came and tried to teach Grandpa to read braille. Perhaps books would entertain him. But his hands shook slightly, and he couldn’t track the raised bumps on the page.

Nuts.

Someone decided pecans were the answer. Grandpa sat at the kitchen table and cracked pecan after pecan. He sorted the meat from the shells the best he could, but someone else, usually Grandma, needed to pick out the stray shells. Another job for her to take on, along with all her other chores that needed completing on a short night’s sleep. The pecans were stored in jars and given to family and friends, all of whom soon had more pecans than they could ever use.

Grandpa kept cracking nuts, but he didn’t sleep better. Nights were restless and his mind paced, although the rest of him couldn’t. Grandpa was certain dawn must be coming soon, even though it was hours away, and he would ask, “Olive, you awake? What time is it?” And Cabela, certain the day should begin even though it’s hours away, stares at me most mornings as if to say, “You awake? It’s got to be time to get up.”

On the last weekend of January, my city celebrates winter with an Ice Festival, and as part of that celebration, small ice sculptures crop up around town. This year right before the festival weekend, an arctic front showed up carrying a couple of bags of windchill and settled in for a week like our town was an Airbnb.

I wasn’t bothered that Mr. Arctic Front crashed the festival because I never attend the outdoor tribute to winter. It’s not because I don’t like snow and cold, but I embrace it differently. I honor winter by reading, writing, walking my dogs, feeding the birds, baking, and marching briskly from my car to whatever building I’m entering. But on Saturday night, I enjoyed the festival’s closing fireworks, watching them from my kitchen window while sipping raspberry hibiscus tea with honey.

After the Ice Festival was over Mr. A. Front stayed on for the week. Each day his mood descended into a deeper frigid funk, deep enough by Friday morning to cause scads of school districts to either delay their start by two hours or completely cancel classes. The next day Mr. Front stuffed the windchill back into his bags and left town. The temperature rose to a glorious balmy 25°, and I got an itch to have some fun, which brings me back to the ice sculptures. I decided I needed to photograph each one.

I found the list of businesses that sponsored the sculptures, grabbed my phone, and set out on a mission. It was like a treasure hunt, but without the stupid clues. I’m no good at puzzlers or clues or those math problems with trains leaving stations at different times, going different speeds, and heading different directions. I always wanted to shout, “Take the damn bus or drive or fly!”

Pretending my phone was a righteous 35mm with a telephoto lens of phallic proportions, I fancied myself a photojournalist. (Hey, it’s my Walter Mitty fantasy.) I started my ice sculpture treasure hunt with some coin in the bank because I had already photographed the icy racquetball player in front of the YMCA when I dropped my grandson off at his 3K school on Wednesday, and I had snapped a picture of the sculpture in front of the vet’s when I dropped off a urine sample for Cabela on Friday. Years ago, I played many racquetball games with a college friend at the Y. The vet who takes care of my dogs was a former student of mine, and she has cared for all of our dogs accept the first one my husband and I had. My ice safari would turn out to be a trip down memory lane.

I photographed the tender proposal in front of the jewelry store where my husband and I bought our wedding rings in 1985. The Victorian house was captured in front of the chamber of commerce. It represents Fairlawn Mansion built by Martin Pattison, a lumber and mining baron. After Pattison’s death, his wife Grace donated Fairlawn to be used as a children’s home. Two of my uncles lived there for a brief time after they became orphans.

The cool Tramp wooed the adorable Lady while sharing a sparkly, silver noodle made from a pipe cleaner in front of Vintage Italian Pizza (VIP). A couple of days ago when I ordered a pizza to be delivered, I told the young person who took our order that my husband and I have been ordering pizza from VIP for almost thirty years. “Wow,” he said, “I’ve only been working here for five months.” He didn’t sound old enough to have been doing anything for thirty years. “Don’t worry,” I told him, “you’ll get there soon enough.”

My favorite coffee shop sponsored a frozen hot coffee with chilled steam rising out of the mug. I took a break from my self-imposed photojournalism assignment and went inside to order a decaf latte with a shot of raspberry. Sometimes when I write I get cagey, so I pack up my computer and go to the coffeehouse and write. There’s always at least one other person plunking on a keyboard. We never speak because we don’t know each other, but I feel a sense of community.

The Richard Bong Center chose Rosie the Riveter to represent their museum honoring American veterans. My mother-in-law would have loved the cool-as-ice Rosie because she believed women were smart, capable, and strong.

My grandpa Howard served in the U.S. Army during WWII from January 1941 until August 1945. In 1943, he was wounded in Italy and received the Purple Heart. My sister, one of her sons, and I paid tribute to Howard through the Flag of Honor program started by American Legion Post 435 at the Bong Center. The American flag presented to Howard’s family at his funeral was raised during a short ceremony to commemorate his service in WWII

After photographing the ice sculptures downtown, I headed for Barker’s Island, the site of the festival, to track down more sculptures. When I parked the car, I spotted a large pile of misshaped ice marbles. They were part of the winter festival, but I’m not sure how. I liked thinking about them as giant marbles left behind by Paul Bunyan. I loved playing marbles when I was in second grade, and I could beat all the boys. In fifth grade I played Babe the Blue Ox in a play. I made my own costume by cutting out the silhouette of an ox from cardboard and painting it blue. When I was on stage, I was always behind the cardboard ox, and I had no lines, so I didn’t discover I had stage fright until I played the Wizard in the Wizard of Oz in seventh grade.

Across from Paul Bunyan’s abandoned marbles, were two of the prettiest ice sculptures. I don’t know what they symbolize, but I imagine they have a connection to sailors and ships and open waters. In the left photo in the background is the Seaman’s Memorial, a statue dedicated to sailors who have lost their lives on Lake Superior.

And the Ice Festival throne . . . heavy is the head that wears the crown and frozen is the butt that sits upon this throne.

The Superior Refinery sponsored an ice sculpture. On April 26, 2018, an explosion and fire rocked the refinery, which was owned by another company at the time. Luckily no one was killed at the refinery, and even luckier the explosion wasn’t as bad as it could have been. Because if it had been, everyone within a twenty-five mile radius from the refinery would probably not be around to tell their stories. There was a large-scale evacuation. My mother-in-law, who was suffering from heart failure was in the hospital that evening in a neighboring city, which was less than fifteen miles away, and her husband was with her. It was their 66th wedding anniversary. My husband and I visited them at the hospital. Less than a month later my mother-in-law passed away. But on that night, she had her humor with her, and she quipped, “Well, I won’t ever forget the date of the explosion.”

And on a happier note, my favorite ice sculpture, “The Town Musicians of Bremen,” was sponsored by the animal shelter. As a child, the story by the Brothers Grimm was one of my favorites. Turns out the four famous animal musicians have statues of themselves in Bremen, Germany, the Lynden Sculpture Garden in Milwaukee, and in front of some veterinary schools in Germany. (You can listen to the story here.)

And the rest of the sculptures . . . Click on the side arrows to move through the slideshow.